THE TRANSLATION MAP v0.02: A USER'S MANUAL

Warren Sack <translation_map@yahoo.com>

Contents

The

Graphical Interface

Creating an account and logging in

Writing and sending a message

Routing a

message

Geographical, Linguistic, Political and

Economic Databases employed by the Translation Map

Searching for messages

Translating and editing a message

Viewing a translation

Replying

to a message

Viewing replies

Printing and folding a message

You can find the Translation Map at the Walker Art Center's website,

here, at this address: http://translationmap.walkerart.org. The

home page contains a few comments concerning our general approach and

why we have built the Map. Also, listed off of the "login" page

are two links: "login" and "World Map."

The

Graphical Interface

Clicking on the "World Map" opens a moving image of the world

constructed from about 450 satellite photos.

In the upper righthand corner of the world map, you will find a

latitude and a longitude. Immediately below that is a list of

countries. In the example shown here, the latititude is 32 degrees

north; the longitude is 110 degrees west; the list of countries contains

a single element, Mexico. The latitude and longitude change as you

move your cursor over the map. The list of countries changes too

to reflect the countries that can be found in the area immediately

surrounding the position of your cursor.

The world map is oriented so that east is at the top of the page, west

is at the bottom, north is at the left and south is to the right.

The map "spins" by scrolling to the top of the page, moving off of the

top and then restarting again at the bottom of the page. When you

click on a point on the map, that latitude is magnified and becomes a

wide band running from the bottom of the page to the top. This

design was influenced by the title of the Walker Art exhibition: How Latitudes Become Forms: Art in a

Global Age. The section of the map immediately under your

cursor is outlined in dark blue and is magnified in both a north-south

and east-west direction. The rest of the sections of the latitude

are magnified in the north-sorth direction.

The map will stop spinning for a few seconds to give you time to

look. If you continue to move your cursor, the map will stay still.

Once you have clicked on a section of the map, you can explore the

messages that have been sent to or from this section of the world by

moving your cursor to the righthand of the page. Click the button

labeled <click to list messages>. Clicking on this button

performs a query on the database of messages stored by the Translation

Map system. Before explaining this database and the other means

for querying it, let's look at a second way of accessing the Translation

Map.

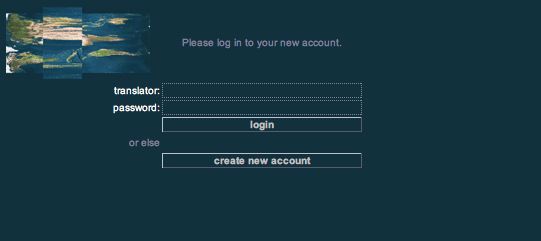

Creating an account and

logging in

This means of accessing the Translation Map, by logging in, allows one

to browse posted messages but also to write and send messages. Off

of the homepage (translationmap.walkerart.org) you will find a "login"

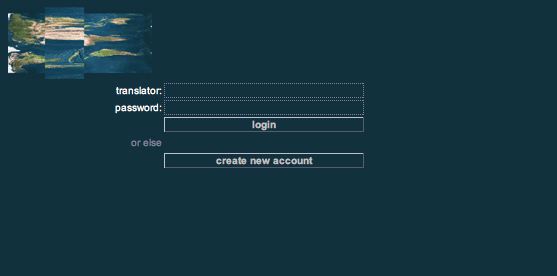

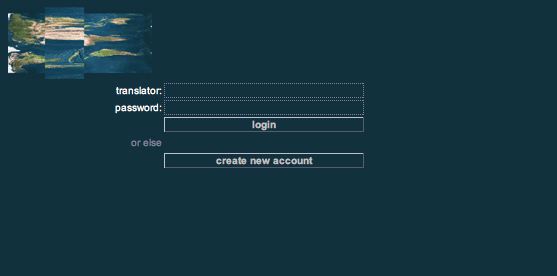

link. Click there and the following page will appear.

If you already have an account of the system, then type in your user

name after the "translator: " label, type in your password, and push the

"login" button. However, presumably, at this point, you do not yet

have an account on the system. So, push the "create new account"

button. Note also the small image of the world map in the upper

lefthand corner of the page. This world map image occurs on this

and every subsequent page. Clicking on this will bring you back to

the homepage of the project.

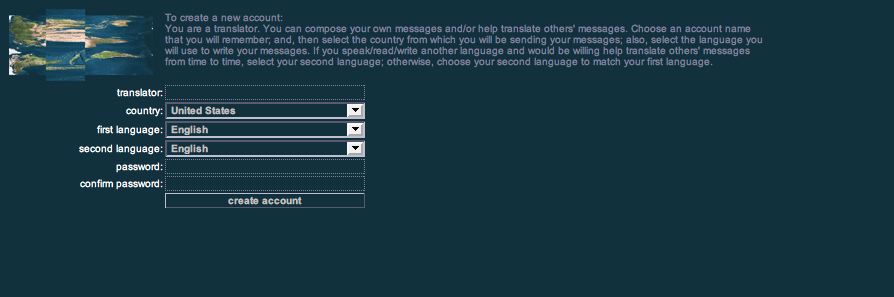

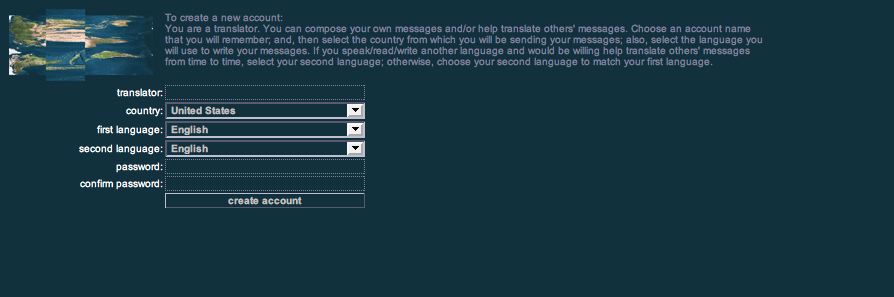

If you click on the "create new account" button, the following page

will appear.

At the top of

the page are directions for creating a new account. Pick a user

name for yourself. This name can be any name you want. Your

user name does not need to have any relationship to your real

name. Next, choose the country from which you will be sending your

messages. You select your country from a pull down menu containing

about 250 countries. After you have selected a country, select a

language. Your "first language" should be the language in which

you will write your messages. You can pick any of the 6000

languages listed on the pull down menu. If you know a second

language and would be willing to help others translate messages from

your first language into your second, or vice versa, select a "second

language." If not, then select your second language to match your

first. Penultimately, choose a password for yourself and then type

it a second time to confirm the chosen password. Finally, push the

button "create account" and you will then see the following page.

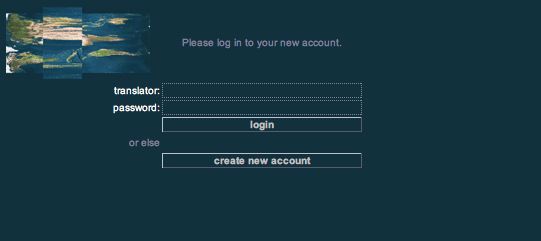

Type in your user name after the "translator: " label; type in your

password, and push the "login" button. Note that, for the purposes

of this project, everyone -- readers, writers and browsers of messages

-- is considered to be a "translator." After logging in, you will

be presented with the following page.

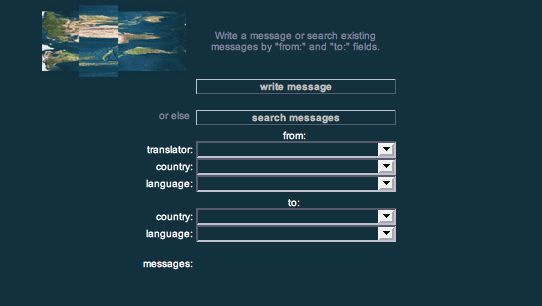

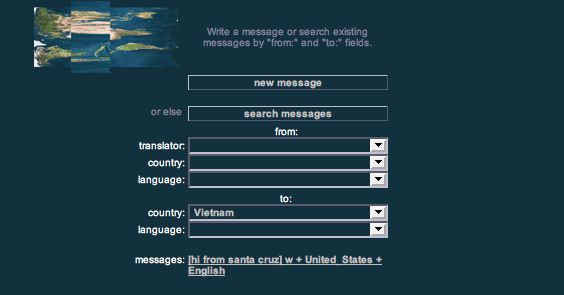

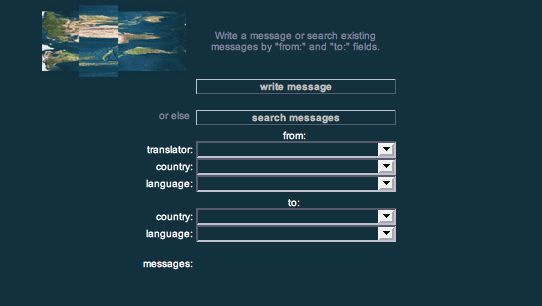

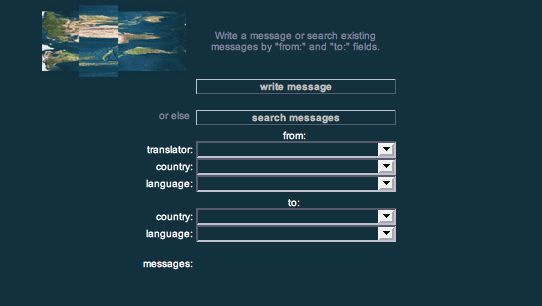

From this page you can either write a new message or query the database

of existing messages. Let's first explore how one writes a new

message. Then, we will return to this page to search through the

messages that have already been written.

Writing

and sending a message

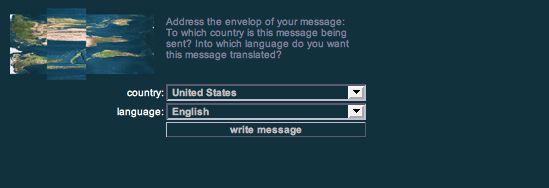

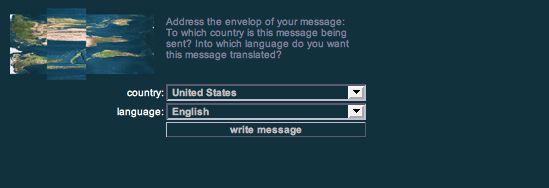

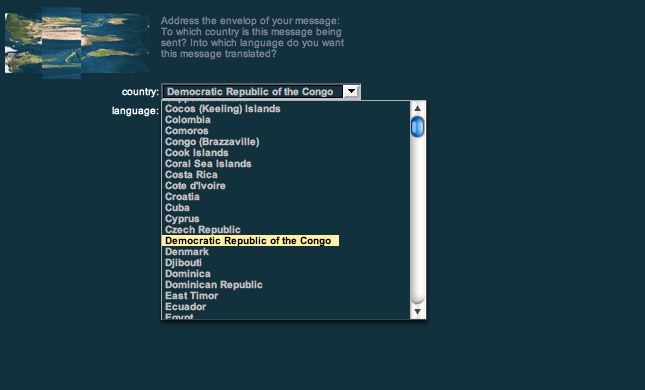

Click on the "write message" button and you will then see the following

page.

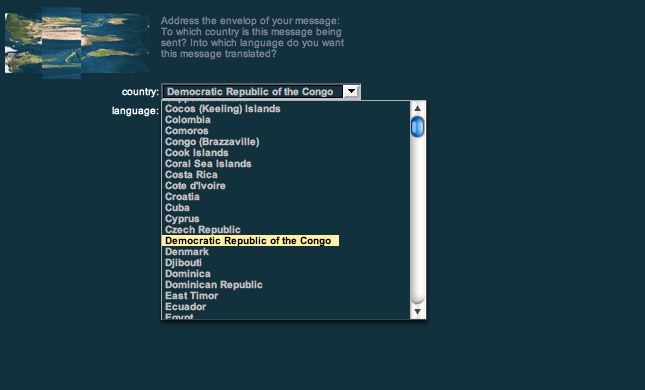

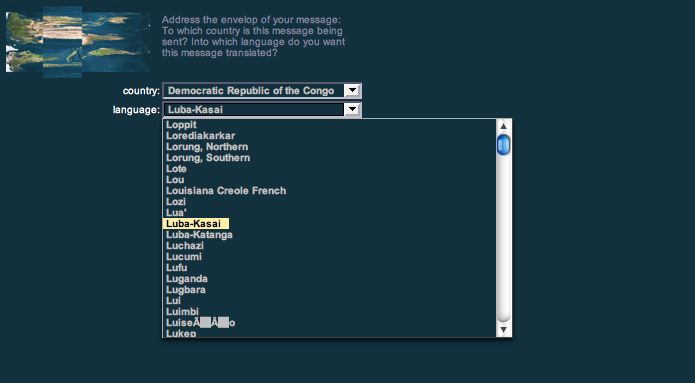

From the menu of 250 countries, select a country to which to send this

message.

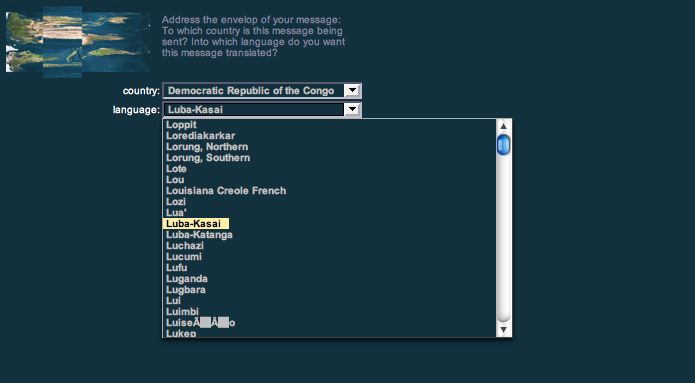

And then, from the menu of 6000 languages, select a language into which

you want this message translated.

Now, press the "write message" button and the following page will

appear.

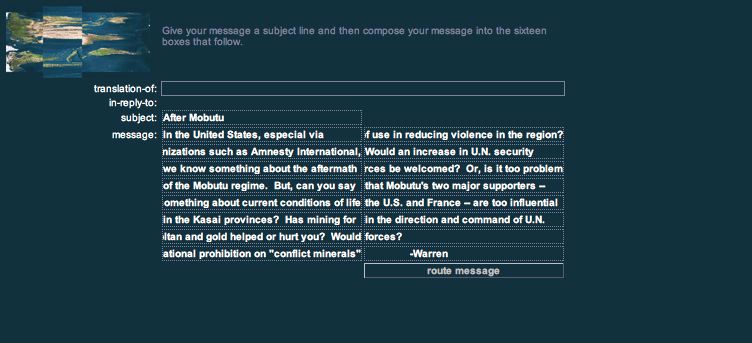

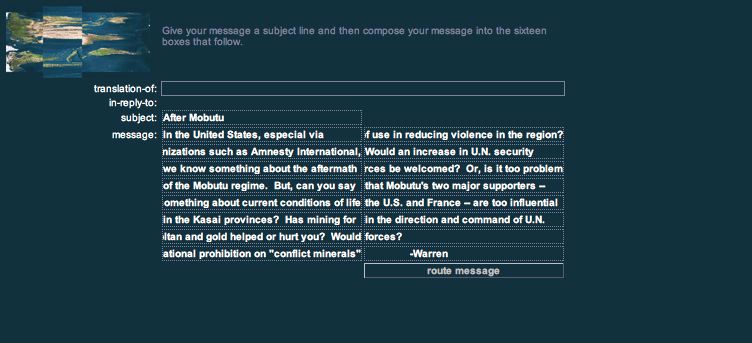

Give your message a subject title and then write the remainder of your

message into the sixteen text boxes that follow the subject. Write

your message by putting only one or two sentences in each text

box. Compose the message in a two column format; i.e., fill in the

text boxes in the left column before starting the text boxes in the

right column. Below is an example message. Note that some of the

text boxes contain more text than is displayed on the screen. Each

of the text boxes can contain entire paragraphs of text if

desired. Or, any or all of the text boxes can be blank.

Compose your message so that each of the sixteen boxes contains some

"logical" unit of your text. A "logical unit" might be a word, a

phrase, a line of poetry, a sentence, a paragraph, or even several

paragraphs. The rationale for this segmentation of the message is

to allow others -- who might later help you translate the message -- to

work on one part of the message without having to tackle the entire

thing. So, it is your job, as the message author, to decompose the

message into parts that might be read individually.

Routing

a message

Now, when you press the "route message" button, the Translation Map

system will attempt to compute a route for the message that will take it

from your geographical location to the destination specified by you;

and, will attempt to find a route that builds a "bridge" between your

language and the desired target language that you specified.

For example, to send a message from the United States to France written

in English to arrive translated into French, the system will attempt to

find a route where English/French bilinguals can be found. The

system computes a number of possible routes and allows you to select

which one (if any) you would like to try. Thus, for the English to

French example, one possible route will be through Canada since a number

of Canadians speak both English and French. The point is for the

Translation Map to assist you in finding possible human collaborators to

help get your message translated from one language into another.

You can read more about our general approach on the home page

(translationmap.walkerart.org), but the main point is this: computers

are lousy automatic translators, but computer networks are good

environments for supporting the collaborative authoring and editing of

documents. So, we are trying to build a Translation Map that will

take advantage of the strength of computer networks rather than to

attempt yet another time implement "artificial idiocy"; i.e., to build

an "artificial intelligence" that performs a task poorly -- translation --

that most people find hard to do.

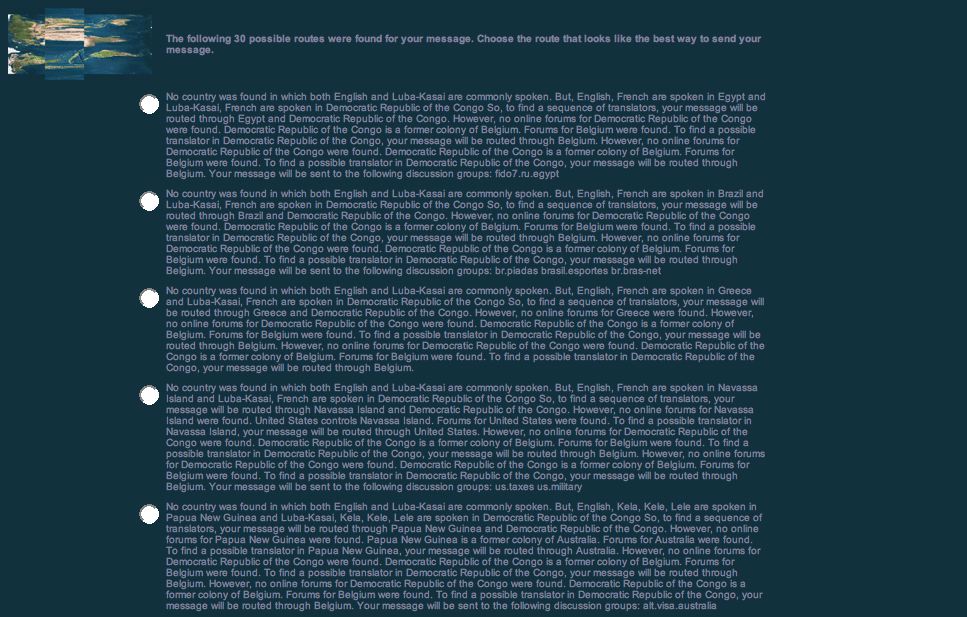

The example chosen here -- i.e., to send a message in English from the

United States to arrive in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

translated into the Luba-Kasai language -- is more complicated than the

English-to-French example described above. And, consequently, the

possible routes for the message computed by the Translation Map are more

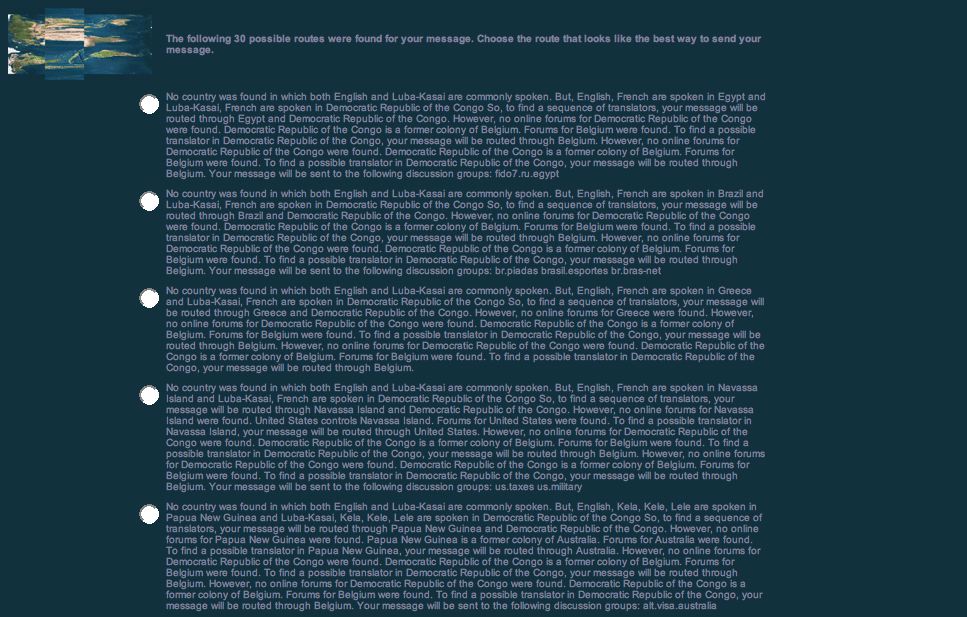

complicated. Here's the top of the page that is displayed after

pushing the "route message" button:

As you can read at the top of the image above, this is simply the top

of the page returned by the Translation Map: the system has computed 30

possible routes for the message and the above displays the first five

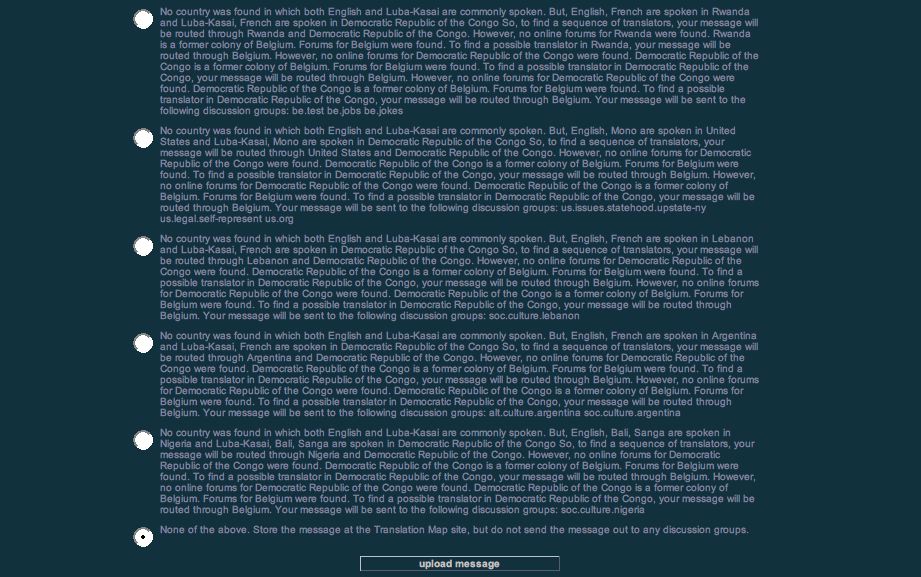

such routes. We will not display the intermediate twenty routes,

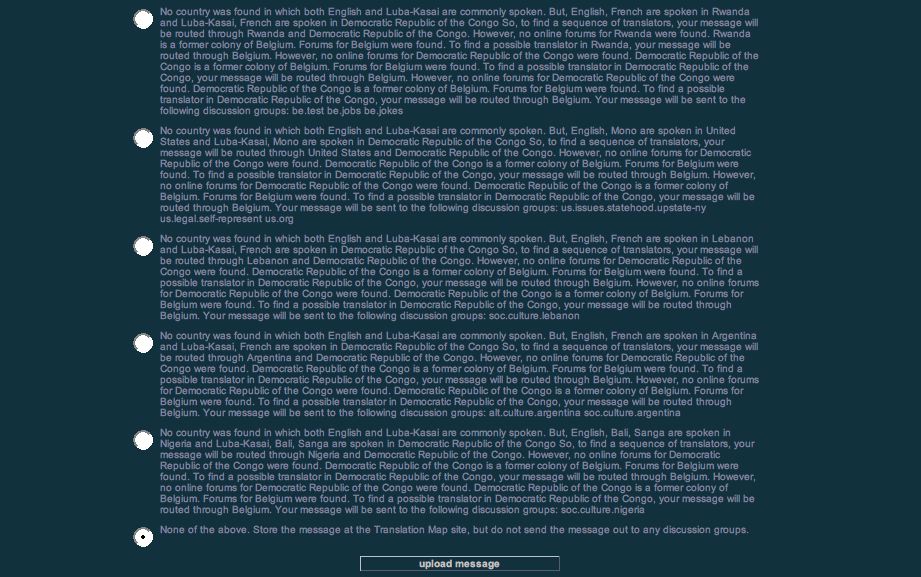

but the final five can be seen in the following image of the bottom of

the routes page:

Examining the first possible route choice one can see some of the work

that the Translation Map does to compute a route. The first choice

output by the Translation Map reads as follows. (I've added

numbers into the text to facilitate the explanation included below).

"(1) No country was found in which

both English and Luba-Kasai are commonly spoken. (2) But, English,

French are spoken in Egypt and Luba-Kasai, French are spoken in

Democratic Republic of the Congo. So, to find a sequence of

translators, your message will be routed through Egypt and Democratic

Republic of the Congo. (3) However, no online forums for

Democratic Republic of the Congo were found. (4) Democratic

Republic of the Congo is a former colony of Belgium. Forums for Belgium

were found. To find a possible translator in Democratic Republic of the

Congo, your message will be routed through Belgium. (5) Your message will be sent to the following

discussion groups: fido7.ru.egypt"

(1) First the Translation Map system searches its databases to

determine if the author's language matches the desired reader's

language. If this was the case -- let's say both were English --

then the system could simply attempt to forward the message to the

desired location. Since this is not the case, the system searches

for a third country in which both the source and destination language

are spoken.

(2) Since no such third country exists in which English and Luba-Kasai

are both spoken, the system search for a third language: a language for

which there exists at least one third country in which the language and

English are both spoken and for which at least one country exists in

which both the language and Luba-Kasai are spoken. The first

language found that meets these criteria is French. It is then

found, in the databases of the Translation Map, that English and French

are spoken in the country of Egypt and French and Luba-Kasai are spoken

in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Consequently, it is

suggested that the message might first be routed through Egypt to get it

translated into French and then sent on to the Democratic Republic of

the Congo to be translated from French into Luba-Kasai.

(3) However, the Translation Map hits a snag because no online forums

are recorded in the database for the Democratic Republic of the

Congo. At present, the Translation Map has a database of several

hundred Usenet newsroups and Yahoo groups. All of these groups in

the Translation Map's databases are public areas of discussion.

With the Translation Map we are attempting to weave together a large

number of public spaces on the Internet. Currently, these public

spaces (e.g., Usenet newsgroups and Yahoo discussion groups) are

isolated from one another by geographical and language

differences. Despite the rhetoric of the WWW futurologists, the

Internet is a divided space; a space largely divided by the borders of

older, political entities: the borders of language , nation and

colonial relations. The Internet is also divided by economic and

class differences. The fact that the Democratic

Republic of the Congo is not well represented as a place on the

Internet should come as no surprise. To route around this

impasse, the Translation Map consults a set of databases it has

concerning economic, religious, linguistic, geographical, and colonial

relations. If the message cannot be sent directly to the Democratic

Republic of the Congo, where might it be sent to get it closer to its

destination?

(4) In this case, the Translation Map finds that the Democratic

Republic of the Congo was previously a colony of Belgium. Since

Belgium is well represented (in terms of online discussion and

newsgroups), the Translation Map proposes to send the message to a

Belgian newsgroup as a step towards sending it on to the Democratic

Republic of the Congo. More about the specific contents of the

databases employed by the Translation Map to make such routing

proposals is in the following section.

(5) After detailing a route that goes through Egypt and then onto

Belgium -- in an effort to get from English to French and from the

United States to the Democratic

Republic of the Congo -- the Translation Map reports that, for the

first step of this route, the message would be sent to Egypt via a

Usenet newsgroup devoted specifically to Egypt; namely, fido7.ru.egypt.

This route (through Egypt and Belgium) is only one of 30 possible

routes that the author of the message can choose. In addition, if

none of the routes look reasonable, one can choose the final

possibility: "None of the above. Store the message at the

Translation Map site, but do not send the message out to any discussion

groups."

If, however, one of the thirty possible routes is chosen, then a link

to the message will be sent to one or more discussion groups. The

message's sender will appear to be you, or rather, will be stated as

coming from your, chosen user identification for the Translation

Map. In this case, my user id is "ww" and so, if I chose the

first possible route, a message like the following would be delivered

to the Usenet newsgroup fido7.ru.egypt:

----------------------------------------------------

Newsgroups:

fido7.ru.egypt

Subject:

After Mobutu

From: ww

The text of

this message can be found here:

http://translationmap.walkerart.org/cgi-bin/tm_view_message.pl?MESSAGE_ID=Sat_Sep_20_2003_1800_18_51_23_966150

It was

written in English and sent from the United States. The message

is addressed to Luba-Kasai speakers in the Democratic

Republic of the Congo. Please forward the message to an

appropriate, public discussion group and/or visit the URL above to

reply to or help translate the message.

Thank you for considering this request.

The following describes why this message was posted to this discussion

group:

No country was found in which both English and Luba-Kasai are commonly

spoken. But, English, French are spoken in Egypt and Luba-Kasai,

French are spoken in Democratic Republic of the Congo. So, to

find a sequence of translators, the message will be routed through

Egypt and Democratic Republic of the Congo. However, no online

forums for Democratic Republic of the Congo were found.

Democratic Republic of the Congo is a former colony of Belgium. Forums

for Belgium were found. To find a possible translator in Democratic

Republic of the Congo, the message will be routed through

Belgium. The message will be sent to the following discussion

groups: fido7.ru.egypt

----------------------------------------------------

The text posted to the newsgroup(s) is intended to be a polite

insertion into the ongoing discussion to indicate the existence of the

message and to ask for help in moving and/or translating the

message. The rationale for posting the message to the given

newsgroup(s) is also included because it is not clear -- short of such

an explanation -- why a message headed to the Democratic Republic of

the Congo should be sensibly posted to a newsgroup devoted to

Egypt. Hopefully, the stated routing rationale also serves to

partially demonstrate the current, fragmented topography of the

Internet.

Geographical,

Linguistic, Political and Economic Databases employed by the

Translation Map

In order to archive, route, forward and store messages, the Translation

Map incorporates data about the world's geography, languages, economic

and (post)colonial relations and public, online discussion

groups. This data was assembled from several sources:

- information about languages and where they are spoken was found

here: http://www.ethnologue.com/web.asp

- information detailing city locations outside of the United States

was downloaded from this website: http://www.nima.mil/gns/html/cntry_files.html

- information detailing city locations within the United States was

downloaded from this website: http://geonames.usgs.gov/gnisftp.html

- demographic information about the countries of the world was

incorporated from this source: http://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook/

- satellite photos of the Earth were found at this site: http://www.fourmilab.ch/earthview/

- lists of geographically- or language-specific Usenet newsgroups

and Yahoo groups were found on newsgroup servers and at yahoo.com.

More

specifically, the databases in the Translation Map detail the following

relationships about each country: common languages spoken in the

country; the country's position on the large, world map; the regions

(e.g, states or provinces) of the country; its land boundaries;

religions; former or current colonizer; its colonies; the amount (in

U.S. dollars) of its imports and exports; the primary export and import

commodities; other countries that are its export and import

partners; GDP per capita; its Internet code; population; literacy rate;

number of television and radio stations; number of radios, televisions

and cell phones posessed by the population; number of ISPs and

estimated number of Internet users; and the Usenet newsgroups and Yahoo

discussion groups devoted to the country.

Much of this data is employed in the routing heuristics employed by the

Translation Map. For example, if a route between countries cannot

be found through a linguistic relation or geographical proximity,m then

the Translation Map uses former and current colonial relations to find

a possible route. If this heuristic does not yield a route, then

it traverses export/import relations to find possible connections

between the countries.

In addition to information about approximately 250 countries, the

Translation Map also incorporates databases concerning about 6000

different languages. For each language, the databases list which

countries the language is spoken in; the online, discussion groups

devoted to the language; and, more specific geographic information

(exact latitude and longitude coordinates) detailing where the language

is spoken.

The next

version of the Translation Map will support the routing of messages

between cities and towns rather than simply between countries.

This will require a new level of detail in the databases that connect

linguistic data to geographical data.

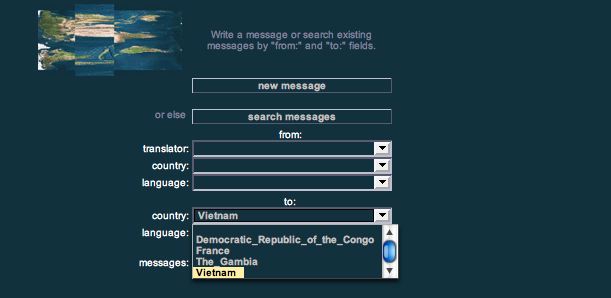

Searching for messages

Once a message has been sent -- or just stored on the

Translation Map site -- it can be found on the site through the

following interface. Note that this is web page that is presented

to you immediately after you log in to the system and also immediately

after you send a message.

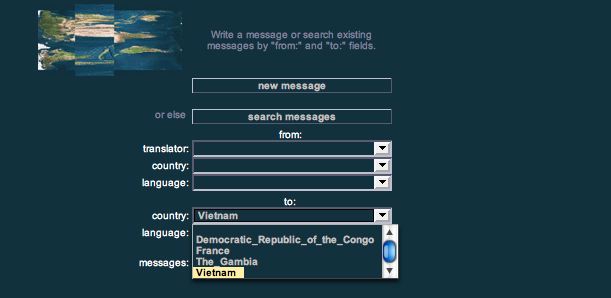

To search for a message stored on the system, use the pull-down menus

shown under the "from:" and "to:" titles. For example, to search

for all messages sent to the country of Vietnam, select Vietnam from

the to/country pull-down menu:

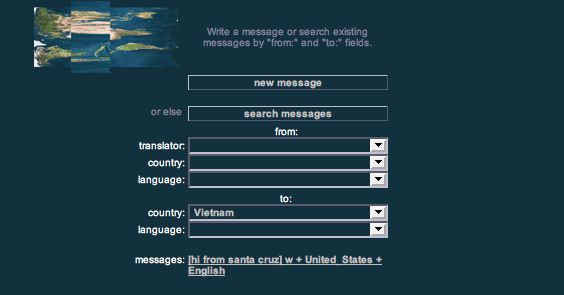

Press the "search messages" button and a web page like the following

will be displayed. In this case, only one message in the system

has been sent to Vietnam. A hyperlink to the message is shown at

the bottom of the page. Clicking on the hyperlink will take you

to a page that shows the text of the message in an editor. Within

the editor (discussed in the next section) you can edit, translate or

reply to the message.

Follow the steps above to search for messages authored or edited by

specific translators, sent from and/or to particular countries or

languages. Selecting, for example, a given translator (e.g.,

"ww") and a given destination country (e.g., the Democratic Republic of

the Congo), will return a list of all messages where the message was

authored or edited by "ww" and where it was sent to the Democratic

Republic of the Congo. In other words, selecting elements from

more than one menu causes the search to be narrowed to only those

elements in the database of messages that meet all of the criteria

selected. In database-speak, the query is a "conjunctive" AND

query rather than a "disjunctive" OR query.

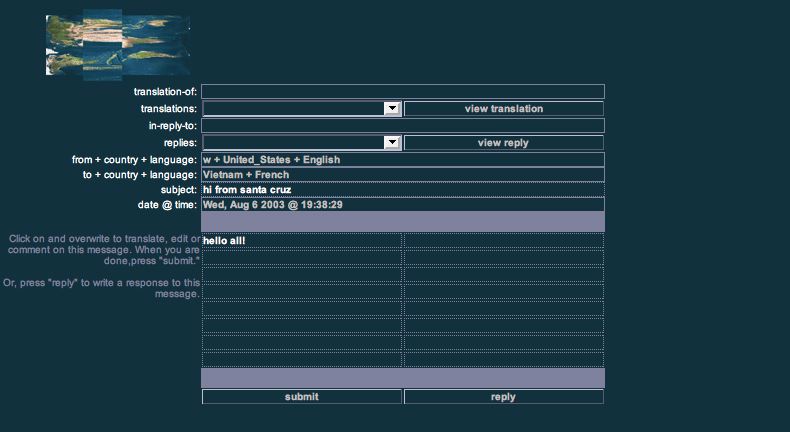

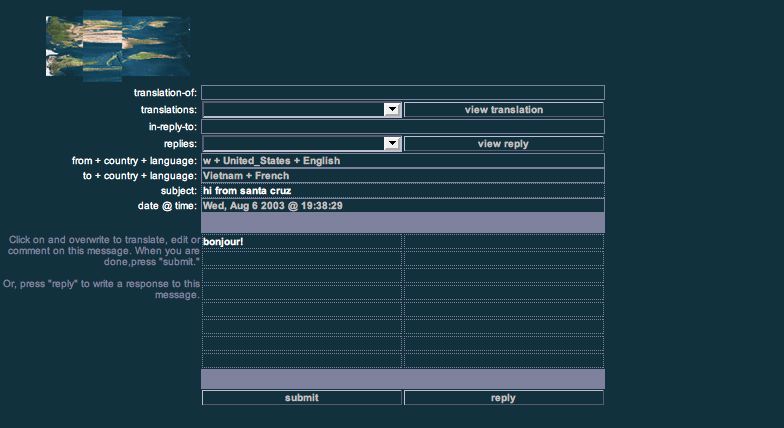

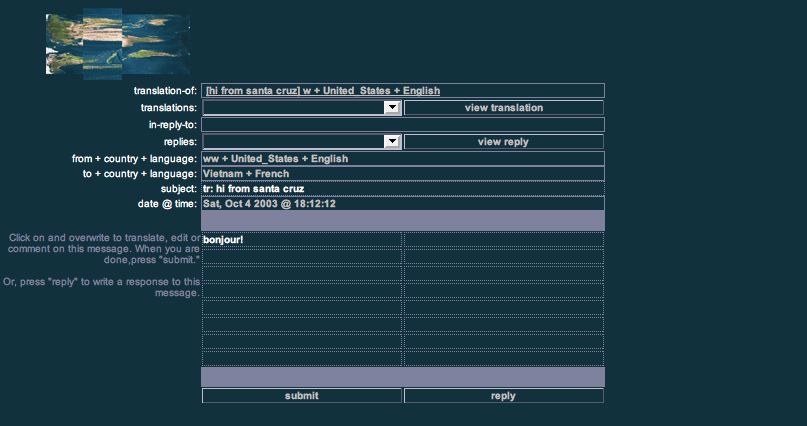

Translating and editing a

message

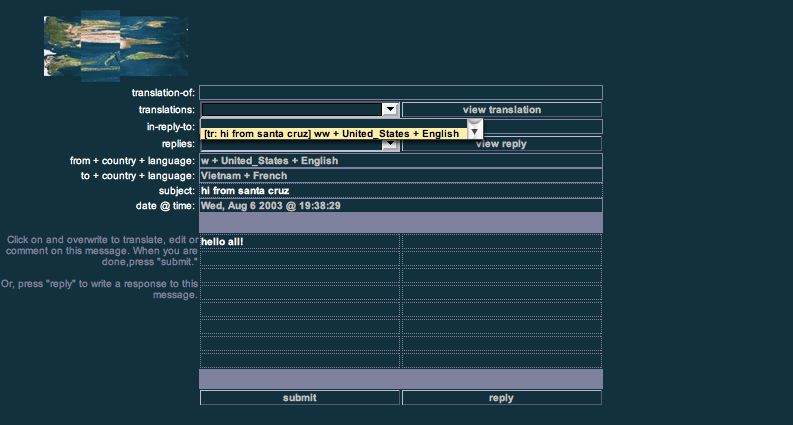

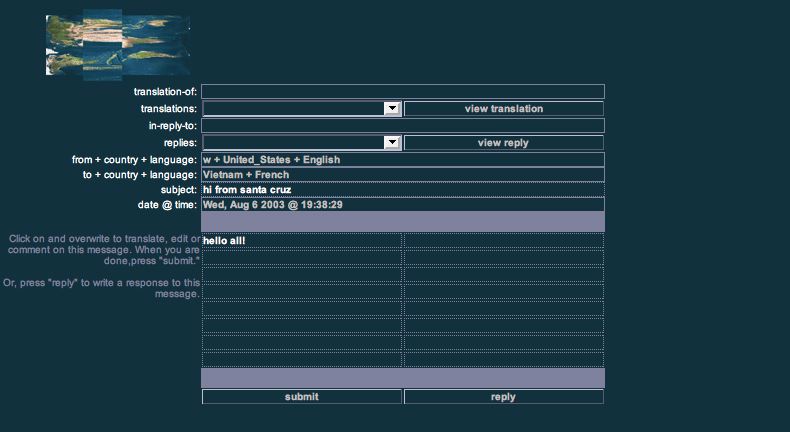

If the search yields a list of one or more hyperlinks, click on one of

the hyperlinks to see the text of the

message in an editor. For example, here is the message I can see

after clicking on the hyperlink shown at the end of the search

explained in the section above.

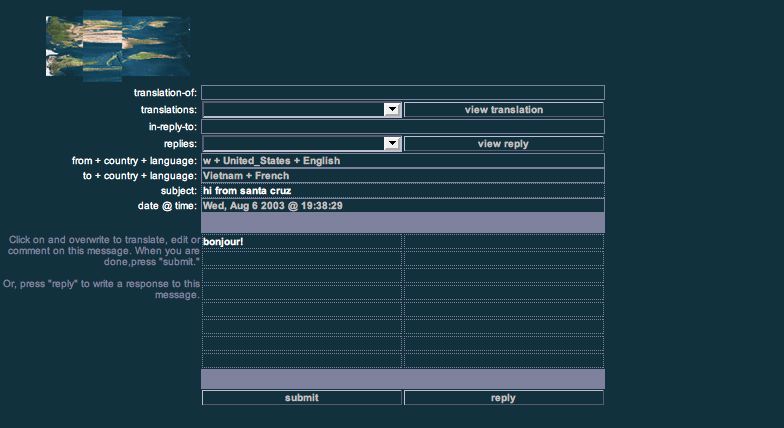

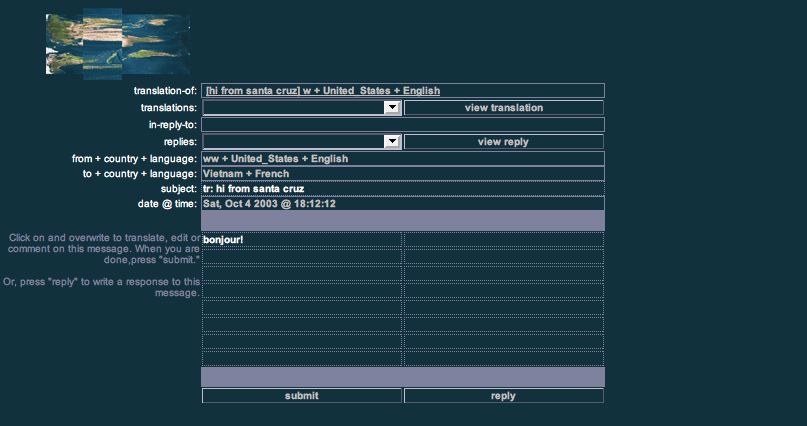

To help translate this message, I can erase the current text of the

message and type the translation directly into the text boxes of the

editor. In this case, I have translated the English phrase "Hello

all!" into a single French word "Bonjour!"

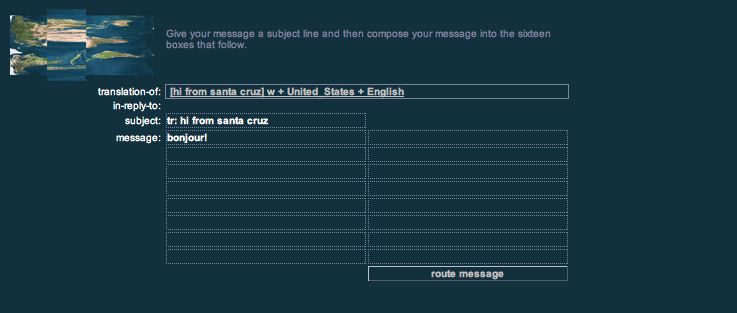

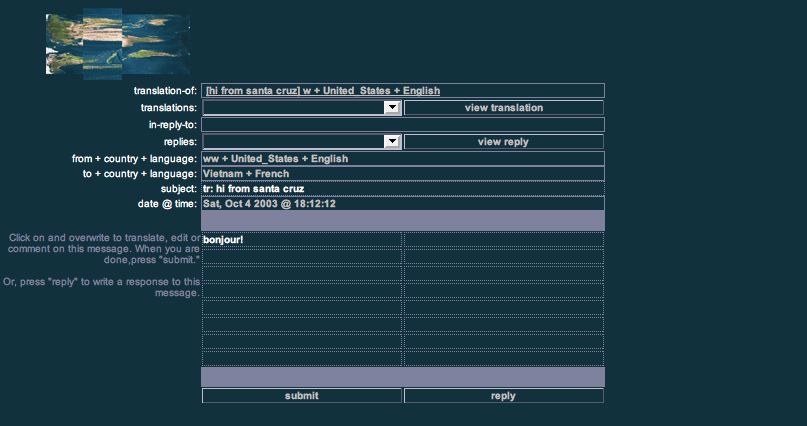

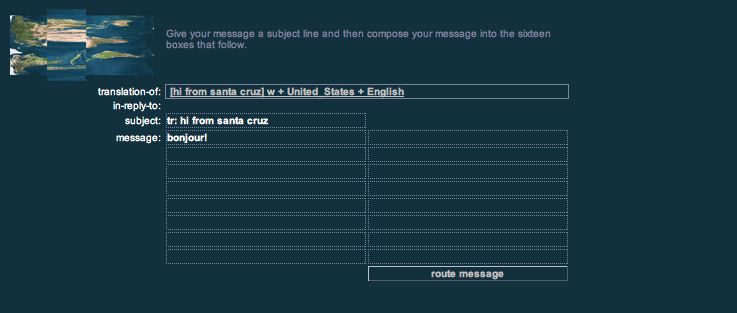

To submit my translation, I click the "submit" button and will then see

the following web page. In this web page I can continue to

elaborate on the translation, or insert more text if I want to edit the

message by expanding it further. Note that a "translation" has

the same status as an original message. When I am finished with

my translation, I push the "route message" button and the Translation

Map will calculate all possible routes (from the United States to

Vietnam) that the translated message might take. I can choose a

route if I want the translation to be sent out to public discussion

groups, or I can choose to leave the translation on the Translation Map

website. All of the options open to the original author of the

message -- as detailed in the section above on "Routing a message" --

are also open to me, as a translator of the message.

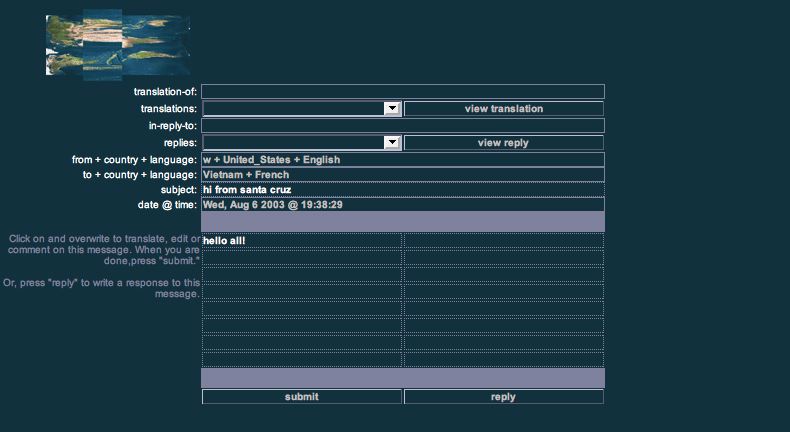

Viewing

a translation

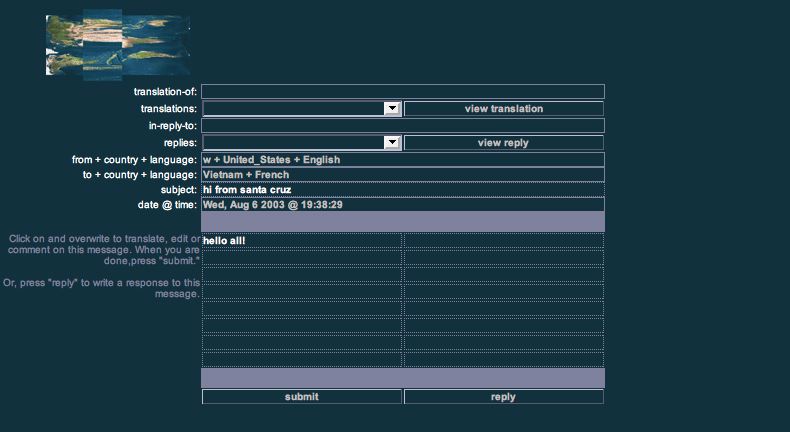

After a translation for a message has been submitted, it can be

found using the search tools (detailed in the section above on

"Searching for messages"). Translations are messages themselves

that can be edited, further translated, corrected, forwarded yet again

out to online, public discussion groups, etc. A translation is

indexed on the Translation Map website under the message

translated. Thus, in the ongoing example from above, the message

translated is this one, the message found on the site authored by the

user "w" that is being sent to Vietnam:

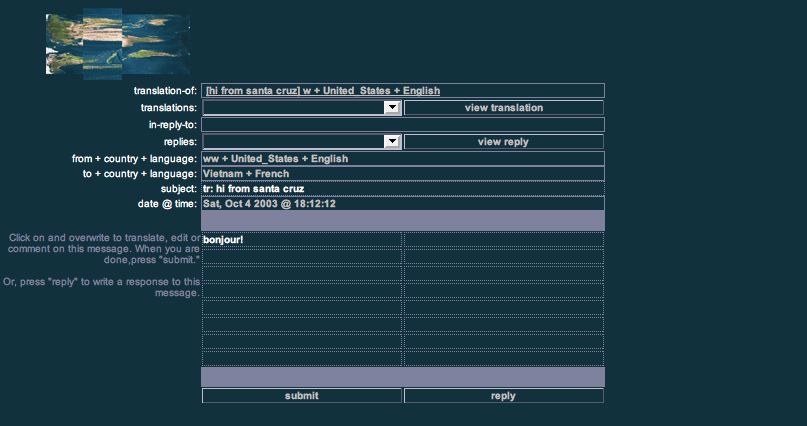

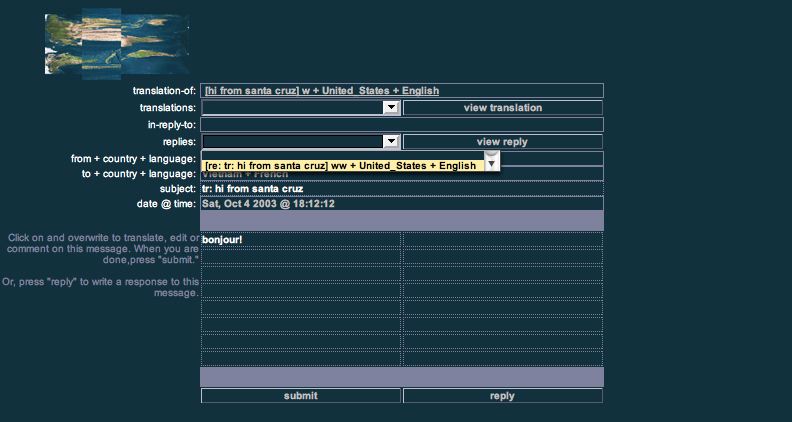

Looking within the pull-down menu of the message, one can now find the

translation discussed above in the section on "Translating and editing

a message."

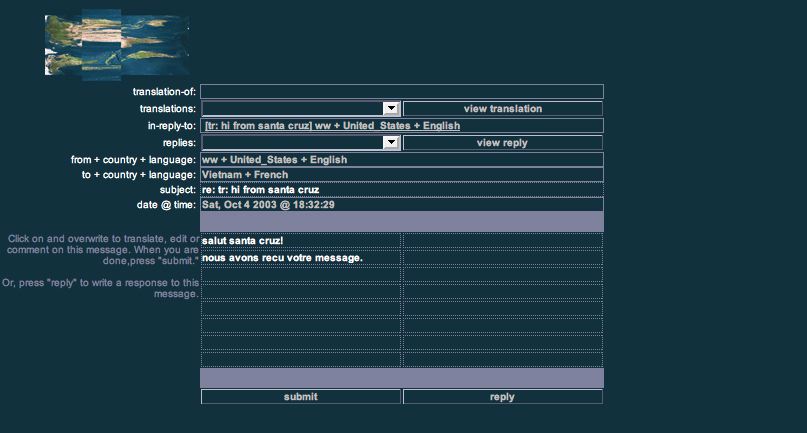

After selecting this menu item and clicking the "view translation"

button, the following message appears. Note that this is the

translation I created to translate the English phrase "Hello all!" into

the French word "Bonjour!" If I want to translate this

translation, or edit it further, I can follow the steps given in the

section above on "Translating and editing a message."

Note also that the translation lists, after the header

"translation-of:" a hyperlink to the original message. Clicking

on this link, brings us back to the original message:

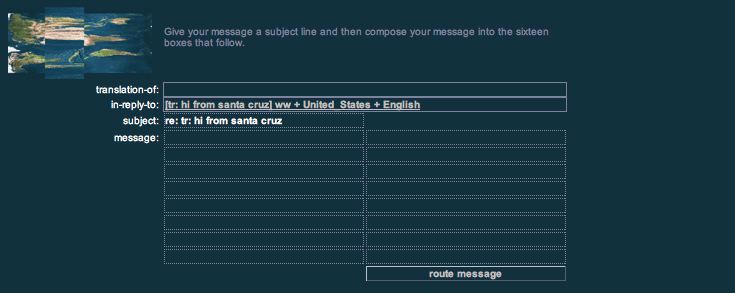

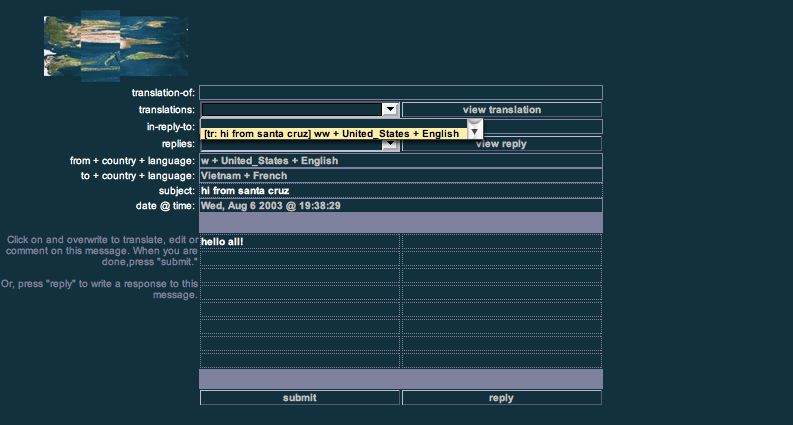

Replying to a message

A message can be translated or edited, but it can also be

replied to. Image that I am a French speaker in Vietnam and I

have found a pointer to the translated message on a newsgroup devoted

to Vietnam. I might click on the hyperlink given in the message

posted to the online discussion group to find the following translated

message:

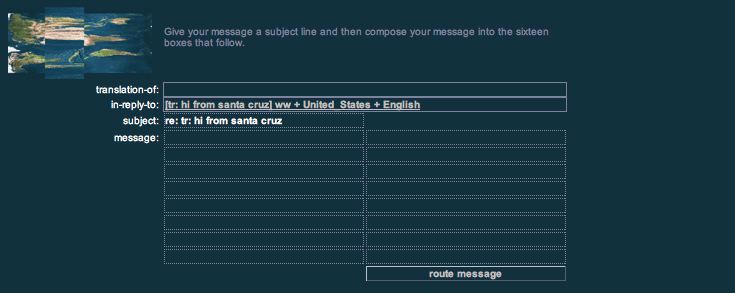

To reply to this message, I click the "reply" button and am presented

with an editable set of sixteen text boxes (just as I am when I author

a new message).

I type my reply into one or more of these text boxes, and then click

the "route message" button in order to route the message back to the

United States, or to simply leave my reply on the Translation Map

website.

Viewing

replies

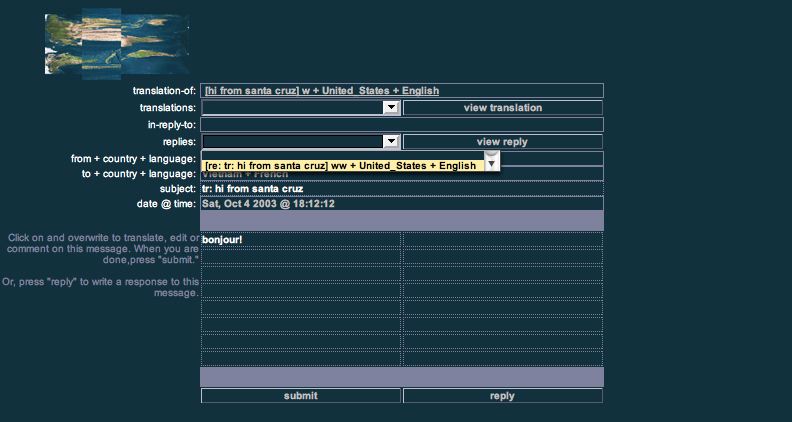

Translations are linked back to the messages that they translate

and replies are linked back to the messages to which they are a

response. Note that, like in email, one message can have many

replies, but a message can only be a reply to a single message.

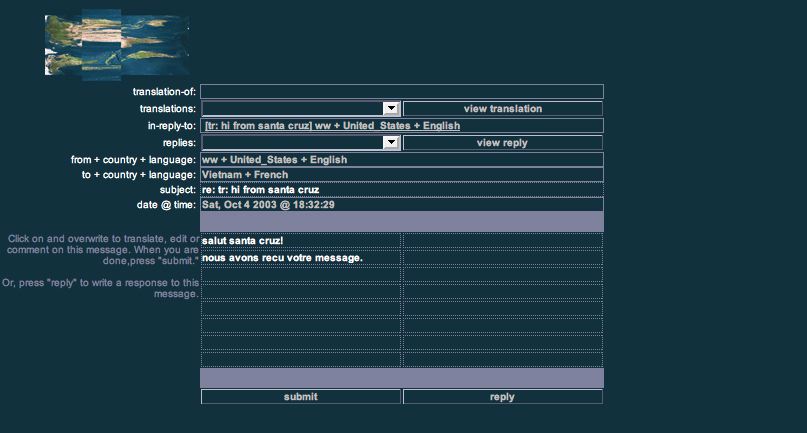

Here is the translated message for which a reply was composed in the

previous section (on "Replying to a message").

Note that if a message has been replied to, each of the replies

will be listed in a pull-down menu that can be found under the

"replies:" header. In this case, only one reply to this message

exists and so only one element can be found in the "replies:" pull-down

menu.

Selecting the reply from the pull-down menu and then clicking

the "view reply" button causes the following web page to be

displayed. From here, one might translate this reply, edit it, or

write a reply to this reply.

Printing and folding a

message

If you play with the Translation Map system for a while and attempt to

send messages to remote areas of the world, you will soon clearly see

that, despite its name, the "Worldwide Web" is not really

worldwide. The Internet only covers parts of the world and has

many missing links. In short, the Internet has limits and when a

message needs to traverse those limits, it will need to be carried by

other means. This will require that a message be printed out and

then either forwarded by postal service, telephone, radio, television,

train, plane, automobile or foot. Consequently, we have

implemented a printing routine so that a message can be printed out and

carried or sent via these one or more of these other means. In

short, the printing routine is in place to allow one to "route around"

the Internet when the Internet is not adequate to the task of carrying

the message where it needs to go.

One possible means of "forwarding" a message is simply to print it out

and hand it on to someone else. However, we all know what happens

to a printed page of text when it gets handed out on the street.

This often happens when ads for stores or products are handed out on

the street: the printed page ends up in the nearest trash can.

To avoid this fate, we have devised a means of folding any printed

message into small fan shape that is more interesting that a flat,

printed page. The hope is that recipients will be more likely to

keep and do something with a folded fan and less likely to simply throw

it out, as they might so do with a regular, printed page of text.

The rest of the section describes how to print and fold a message into

a fan shape.

To print a message, search the message archive for the desired message

(see the section above detailing how to search the archive of

messages). Once you have found the message and it is displayed in

your browser window, push the button labelled "print." This button

will not send the message to your printer because the Translation Map

does not have the permissions to communicate with your printer.

Instead, Adobe Acrobat Reader will open and a version of your message,

in PDF format, will be displayed. If you dont have Adobe Acrobat

installed on your computer, another application capable of opening and

displaying Adobe format PDF files might open the file for you. On

my computer, the Preview application opens the PDF. If you don't

have a PDF reader, you can download one for free from Adobe

(http://www.adobe.com/products/acrobat/readstep2.html). With a PDF

reader installed on your computer you should see a window like the

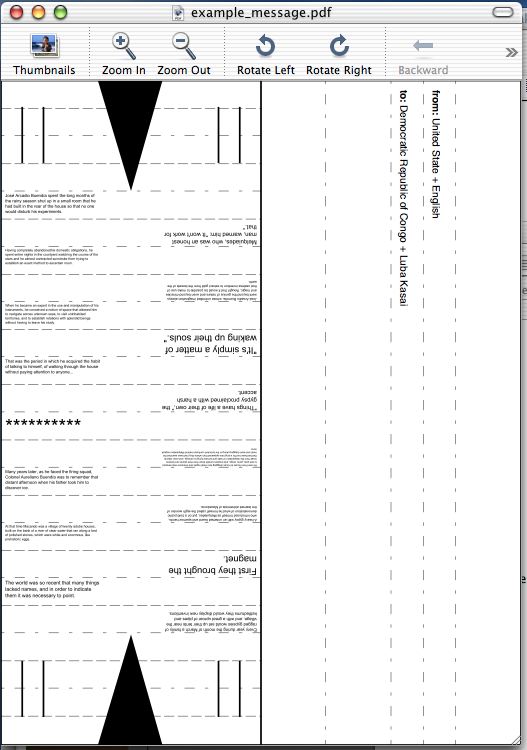

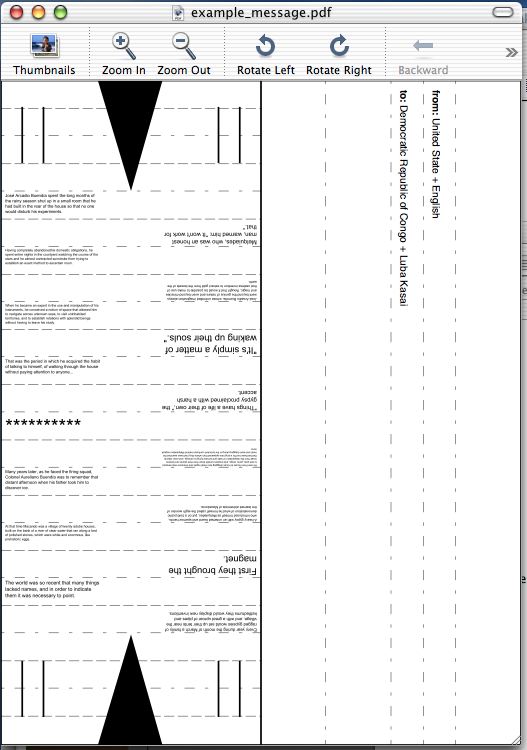

following displayed after you press the "print" button:

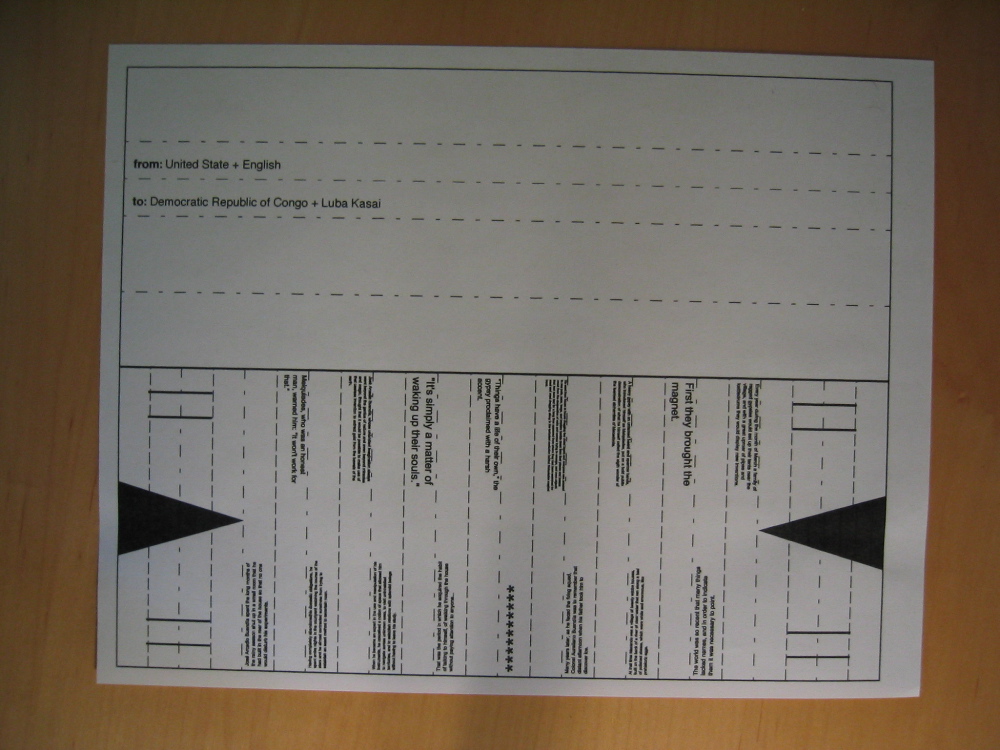

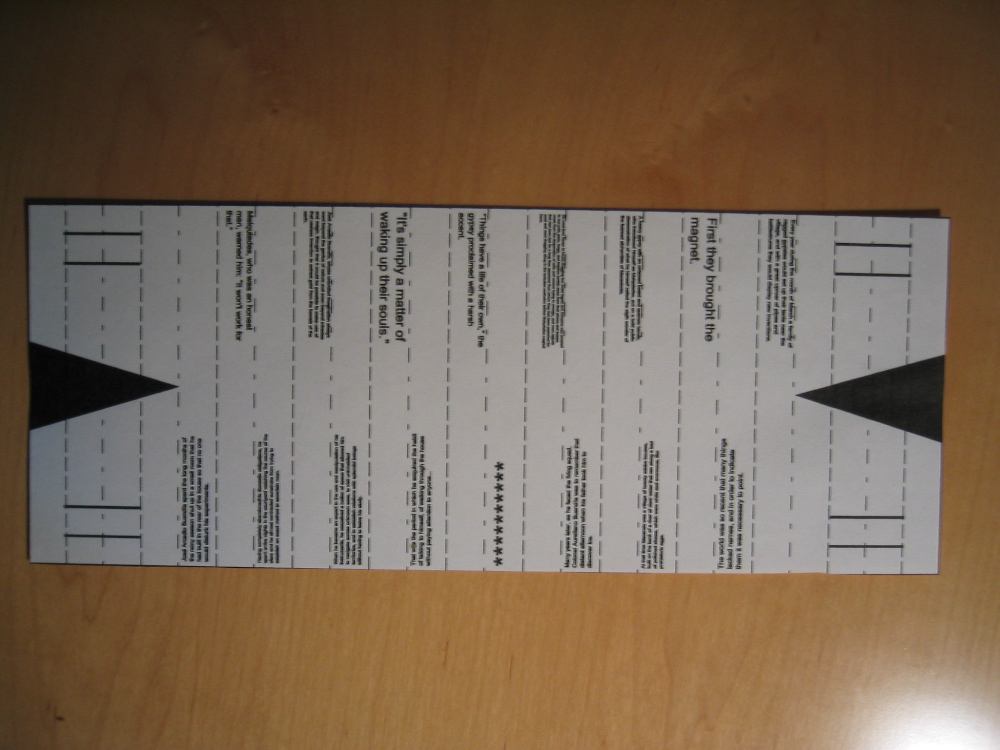

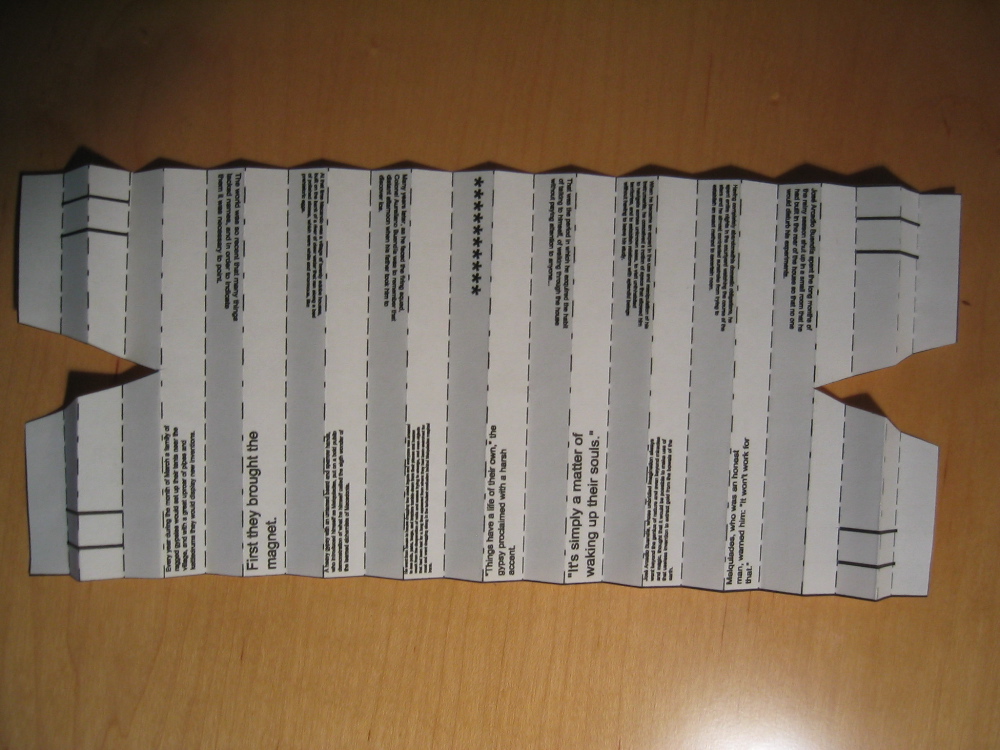

This message is simply an example containing several lines from Gabriel

Garcia Marquez's novel One Hundred

Years of Solitude. Note that some of the message parts are

printed in a smaller type than others. This is because, in the

message editor, large amounts of text were entered into some of the

sixteen text boxes and, in others, only a few words were entered.

The message is printed so that all of the text from each text box

appears in the corresponding printed part of the message; thus, the text

is sized to fit the box. Note also that the first column of the

message is printed right-side up and the second upside down. Once

the message is folded, it will be clear why this is so.

So, from the PDF reader print the message out on your printer.

You should now have a piece of paper that looks something like the

following:

This is the printed form of the message. If you want, you can

fold the message into a fan. What follows are the directions for

cutting and folding a message.

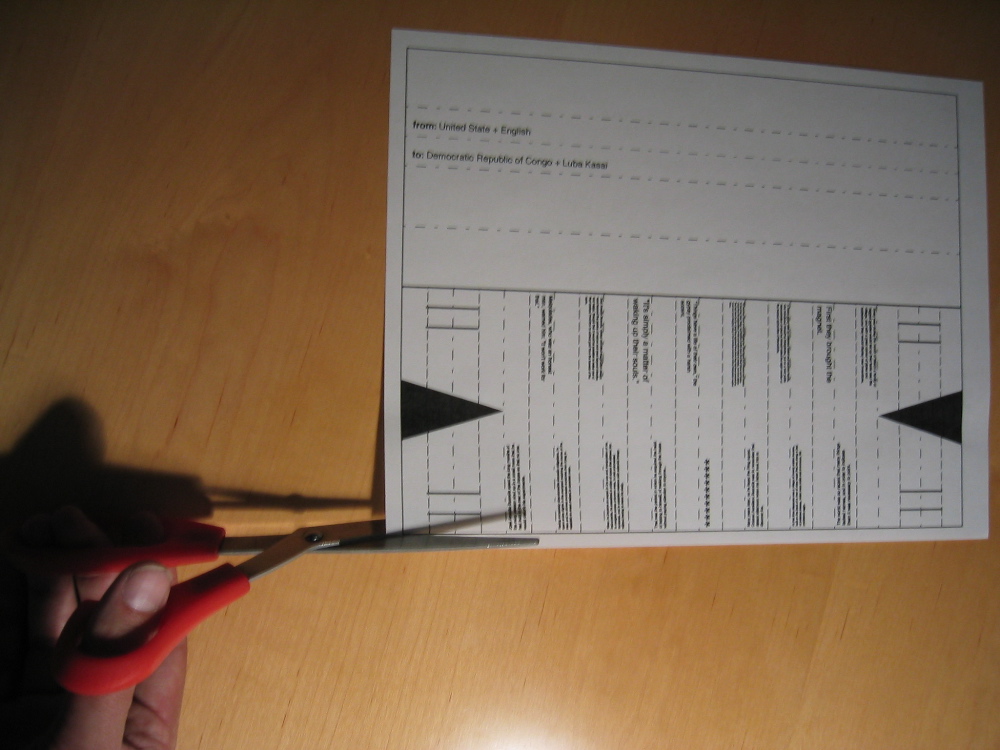

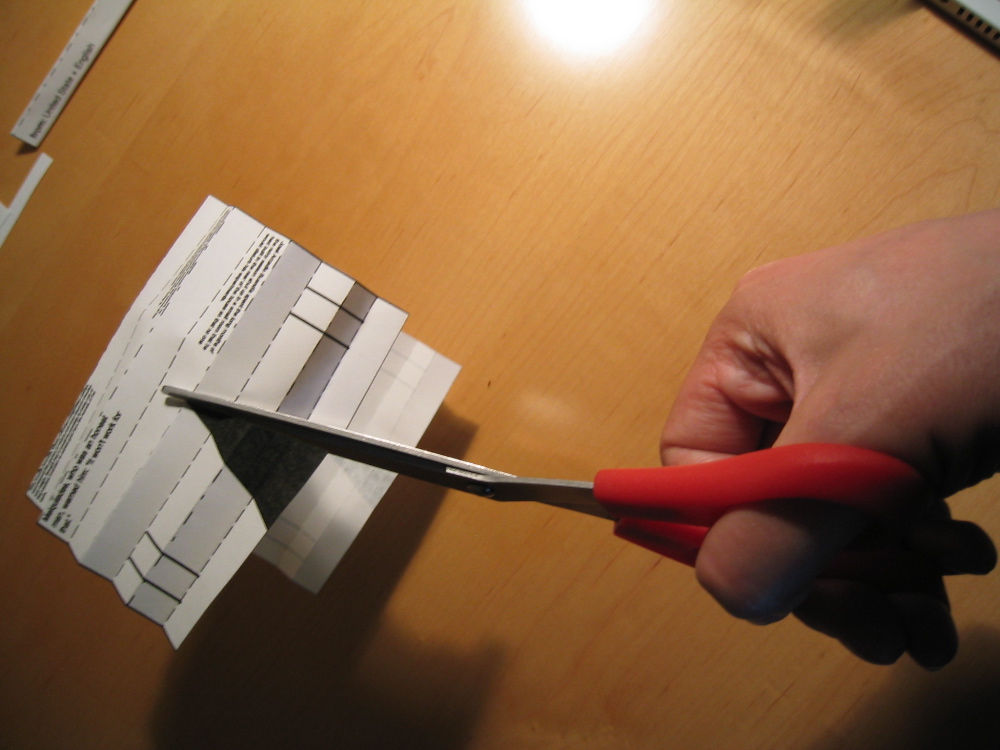

Following the solid line that outlines the the edges of the message,

take a pair of scissors and cut off the edges of the paper.

After clipping off the edges, you should now have a slightly smaller

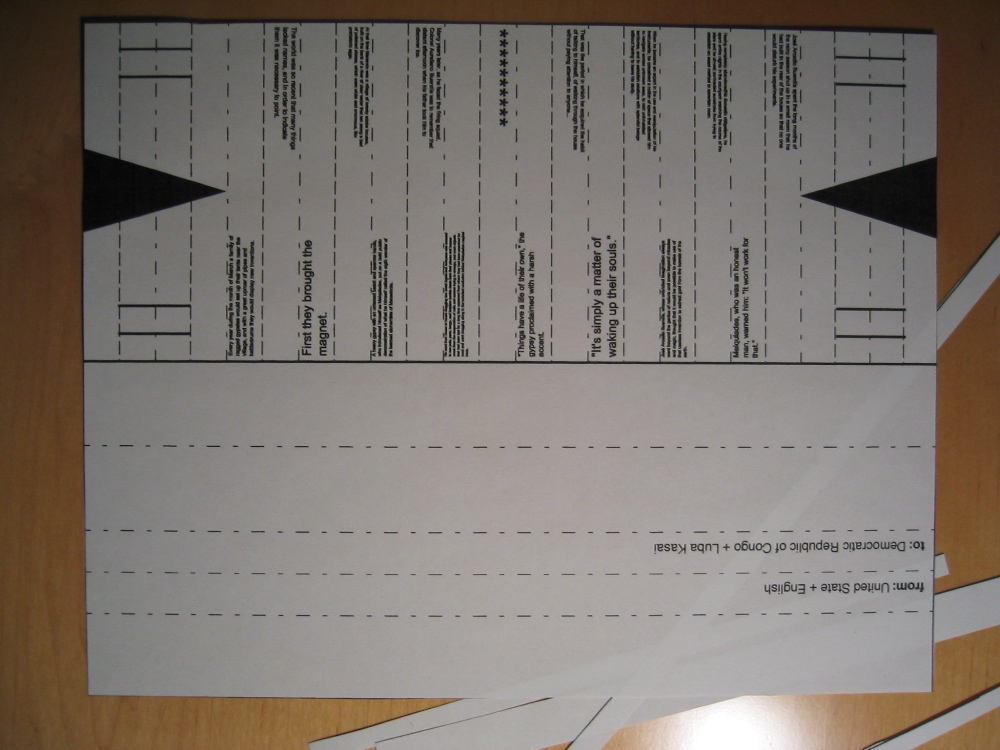

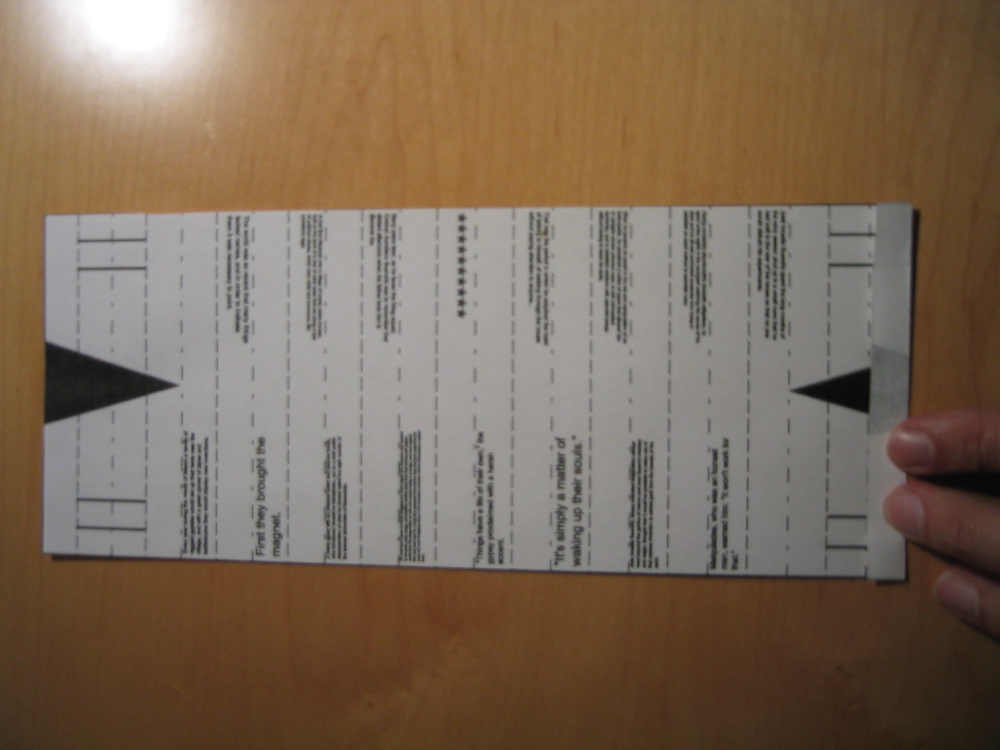

piece of paper that looks like this:

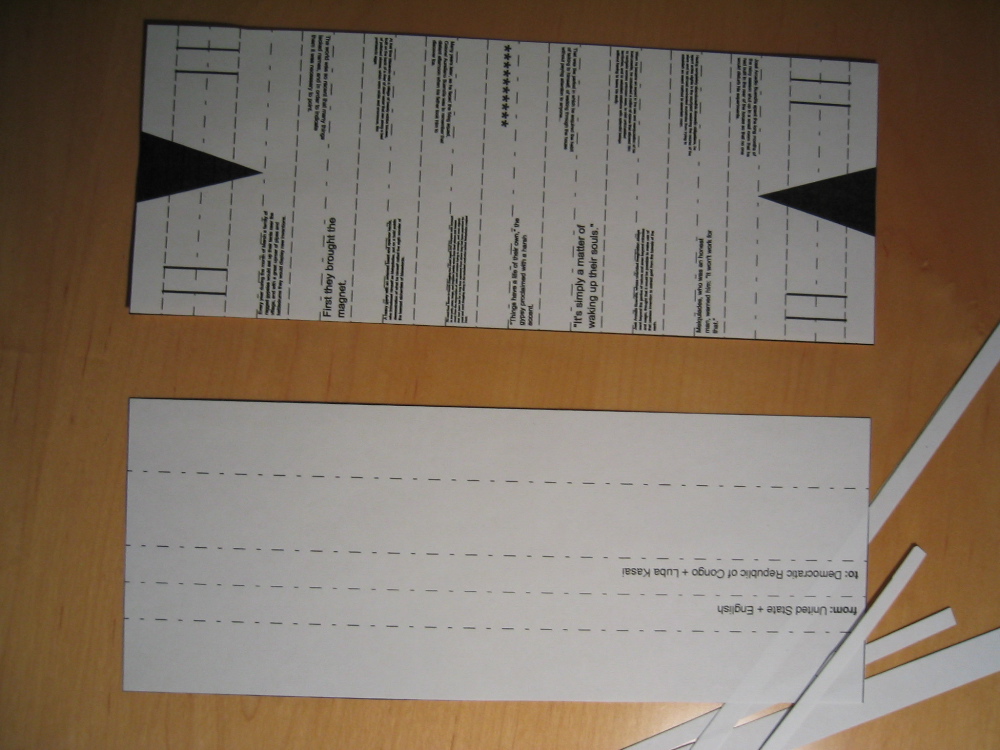

Cut the piece of paper in half, along the solid line printed down the

middle of the page.

Take the half of the page that has four vertical, dashed lines on

it. Fold it in half...

Fold it in half again...

Then, fold it in half one more time so that you have a long narrow

shape like the following:

Put that to the side for the moment and pick up the other half of the

page.

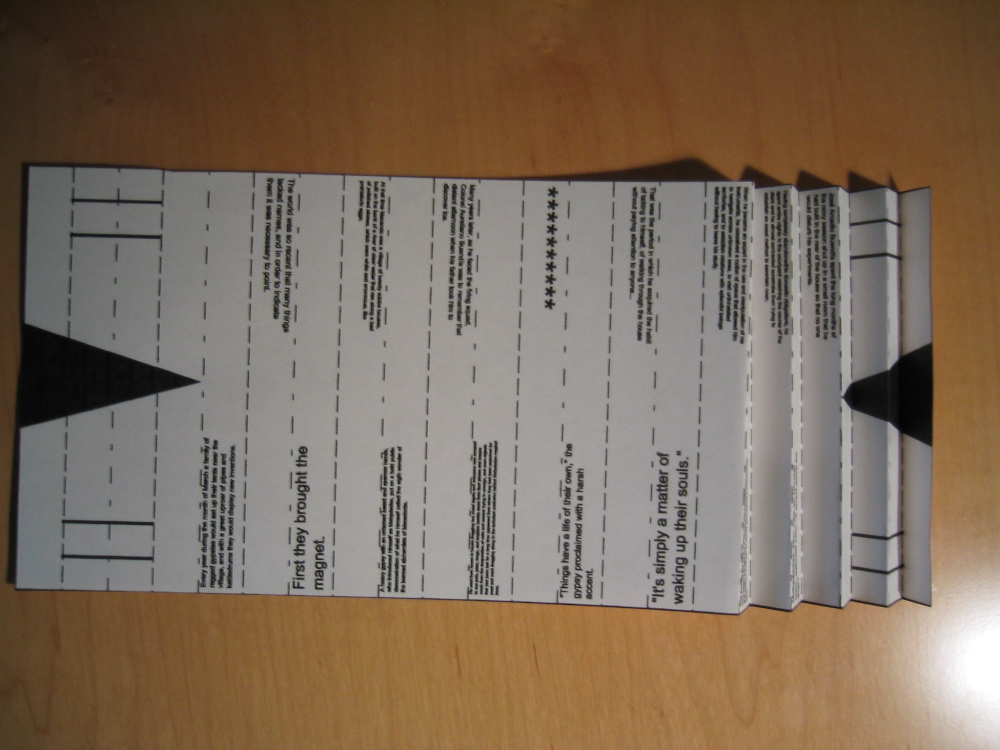

Pleat this half of the page horizontally by folding back and forth

along the dashed lines. The following picture shows the first fold

to be made.

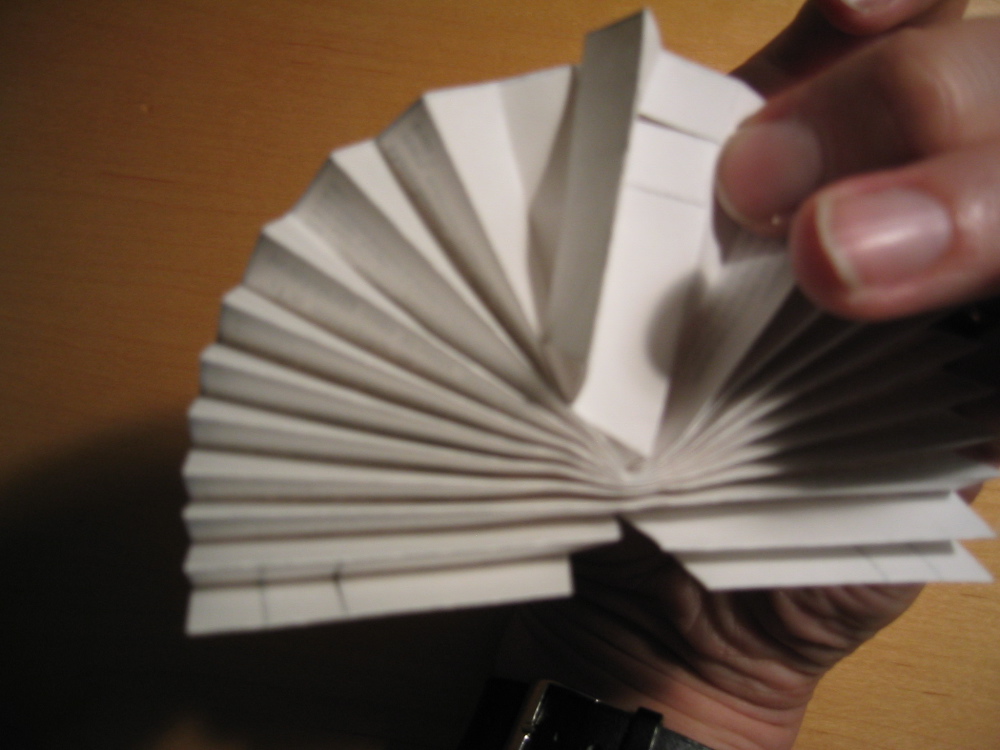

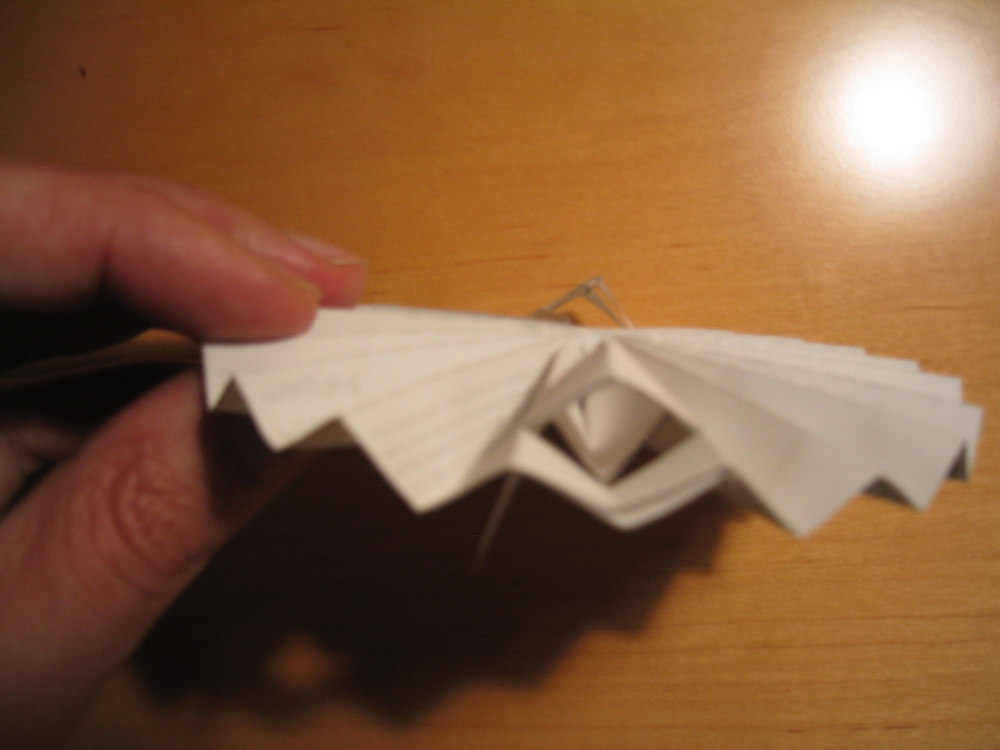

This picture shows what it looks like after I have folded it eight

times.

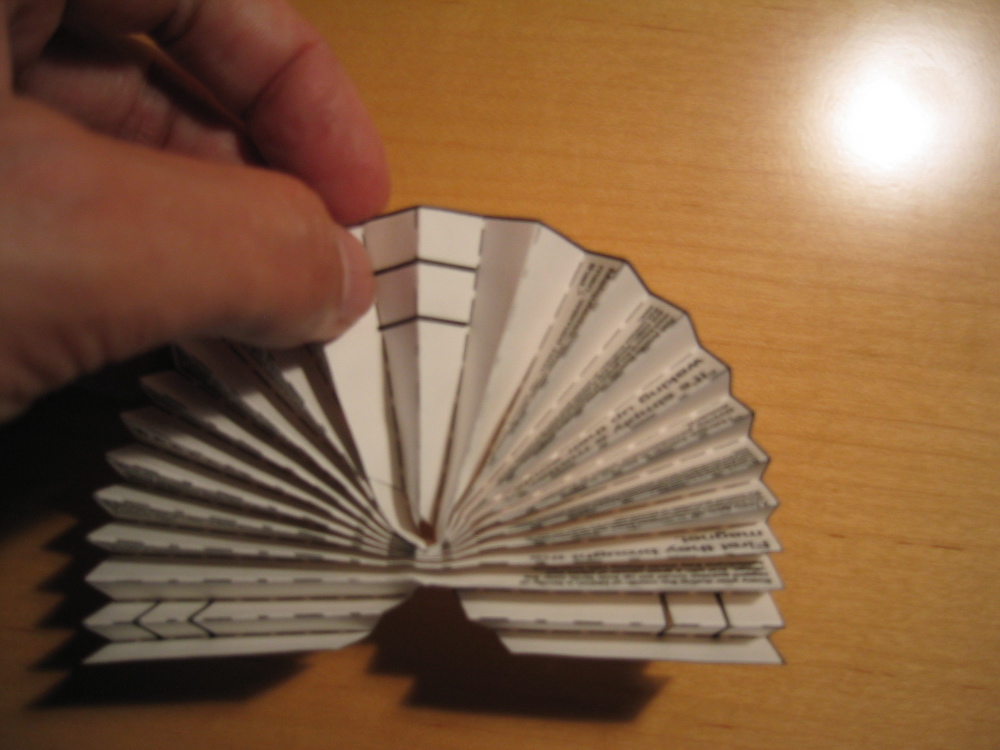

This picture shows it after I have finished folding and the piece of

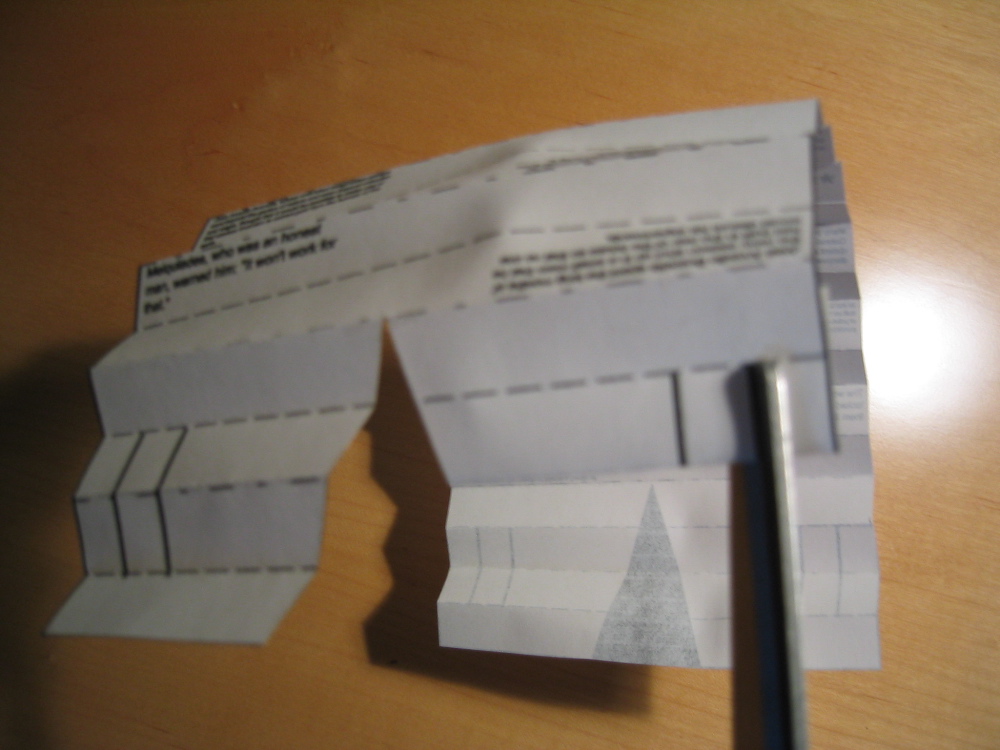

paper is completely pleated.

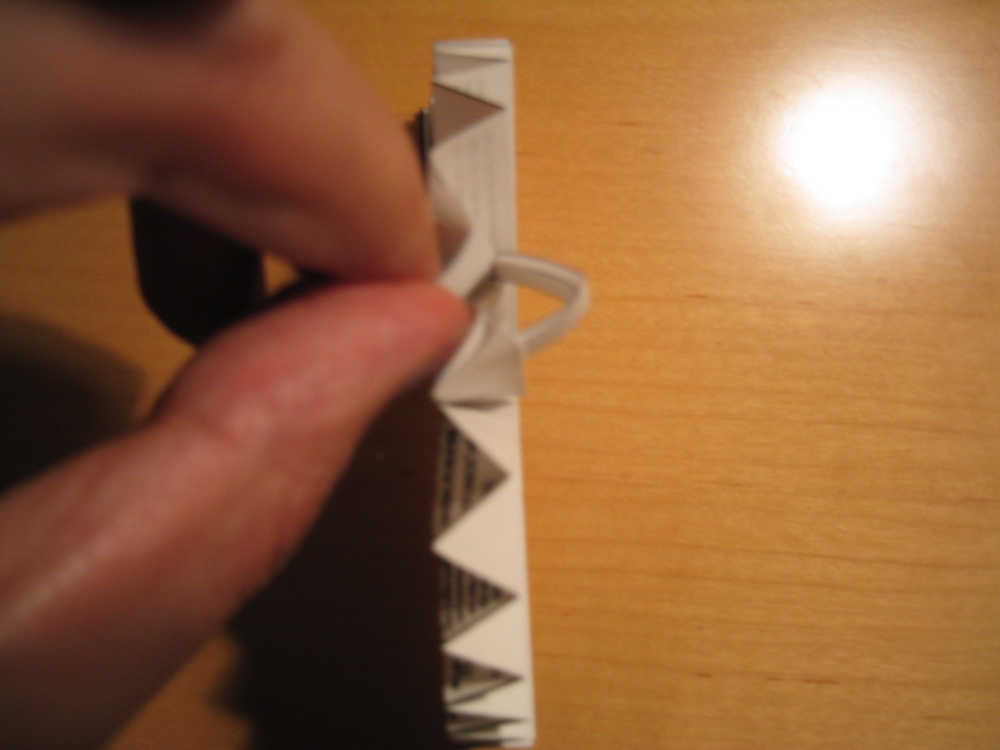

Unpleat the paper slightly so that the two black triangles can be cut

out.

After you have finished cutting out the black triangles, find the the

four short, solid lines to the right and left of the triangle on one

side of the paper. Find the four solid lines on the other side

too. Clip these lines with the scissors so that there are eight

new cuts in the paper.

Once you are finished cutting out the two triangles and clipping the

eight solid lines, the piece of paper should look something like this.

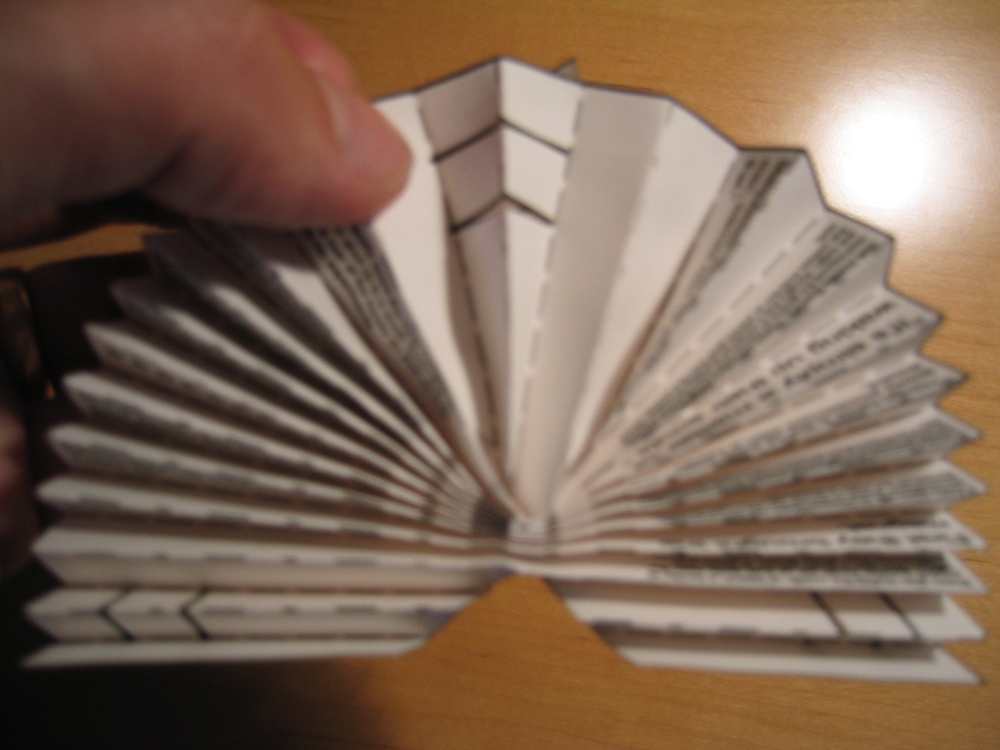

Repleat the piece of paper and pinch one end of it between thumb and

forefinger.

Now, fold the whole thing at the middle, in one direction...

Pinch it again and fold it in the other direction. This will make

the center flexible and ready for the steps to follow.

Take the top fold from one end of the pleated paper and then the top

fold from the other end. Bring them together so that the clipped,

solid lines from each end overlap and so that the message now looks like

a pleated semi-circle.

Turn the message over. Note that the back side of the message is

blank. Now comes the slightly tricky part. Hold the ends

together with one hand and then with your other hand fold the pleats

from one end of the message into the pleats of the other end of the

message.

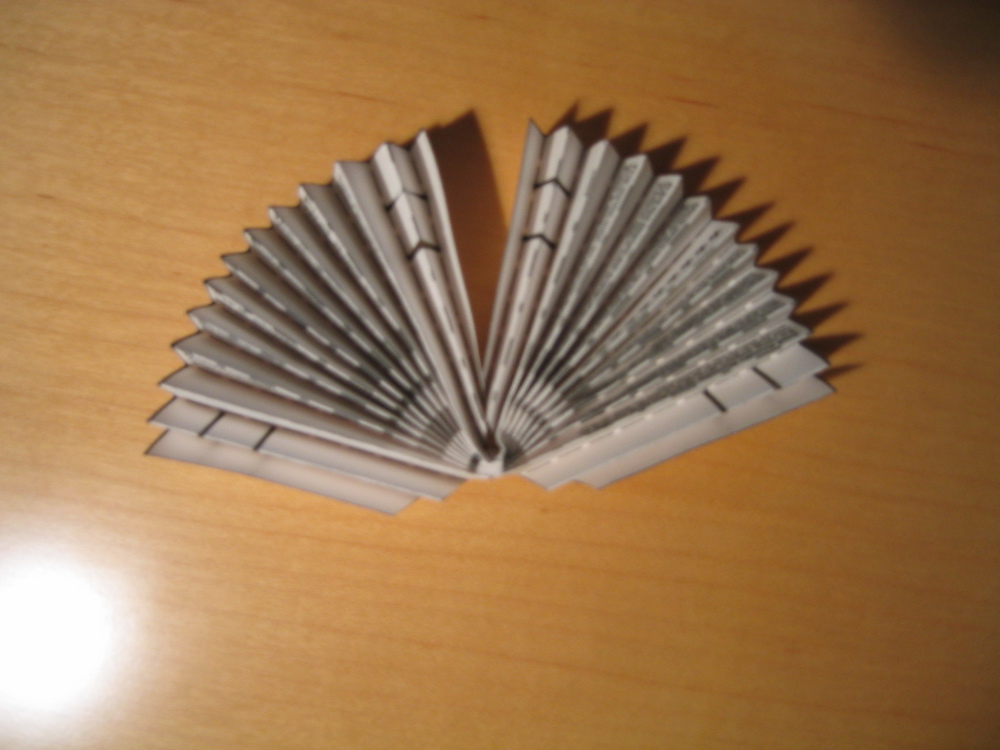

If you manage to fold the pleats of the two ends of the message

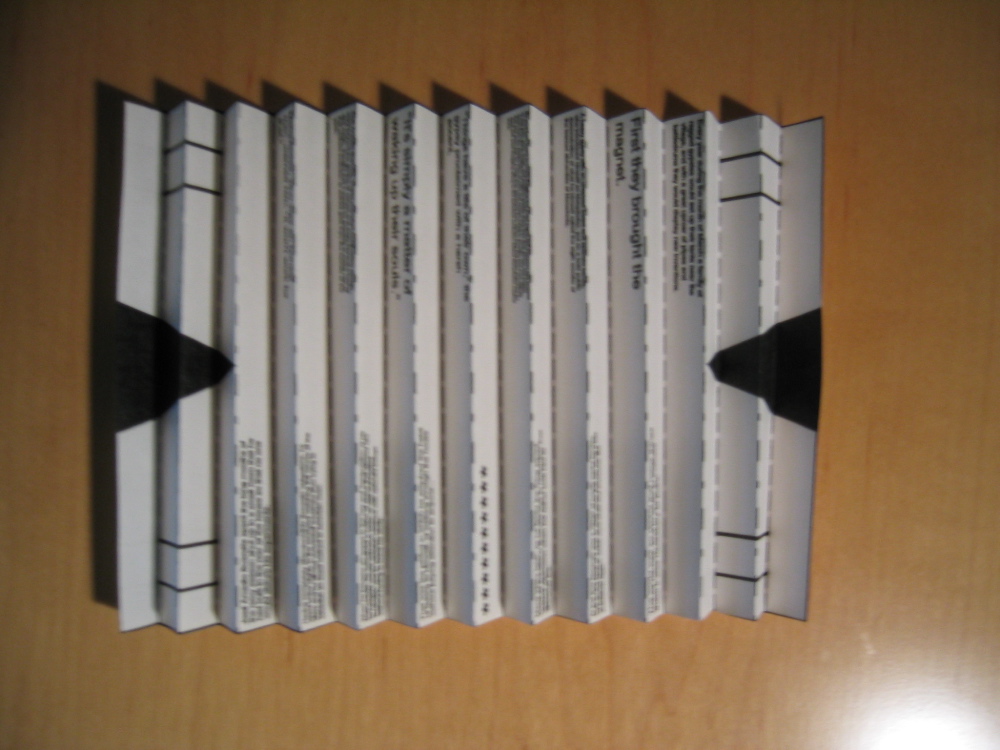

together, you should now have something that looks like this.

Note that

the clipped lines from one end of the message need to exactly line up

with the clipped lines of the other end of the message. Turn the

message over to its front side again. It should look like this:

If the clipped lines of one end of the message are lined up with the

clipped lines of the other end, then it should now be possible to push

down on that part of the pleat and invert a section of the fold, like

this:

Here's what the inverted section of the fold looks like from the

side. There should now be a little "loop" on the back side of the

message.

Repeat the above for the other ends of the message so that, after

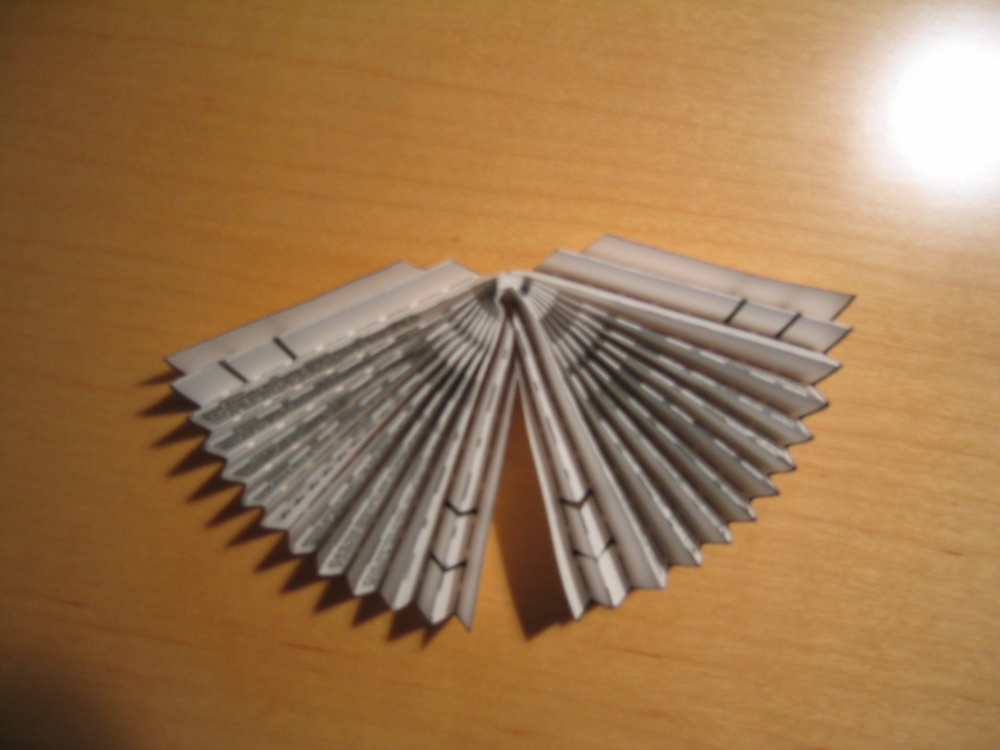

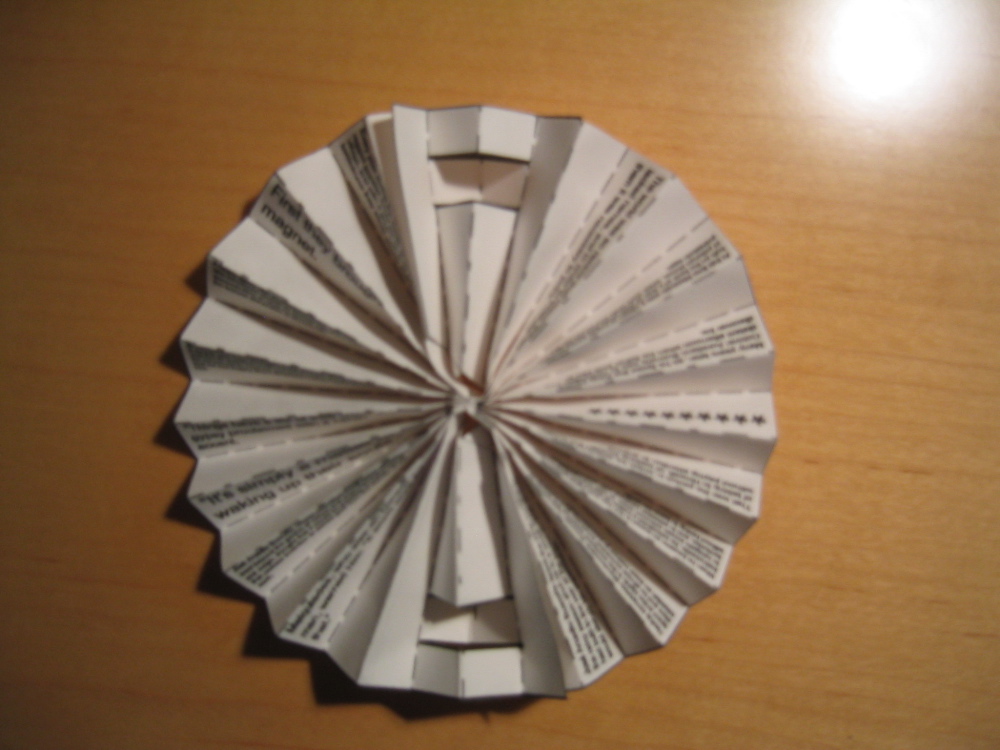

inverting the second set of cuts, your message should have a circular

form and look something like the following:

From the side, the message looks like this, with two small "loops" at

the back of the message.

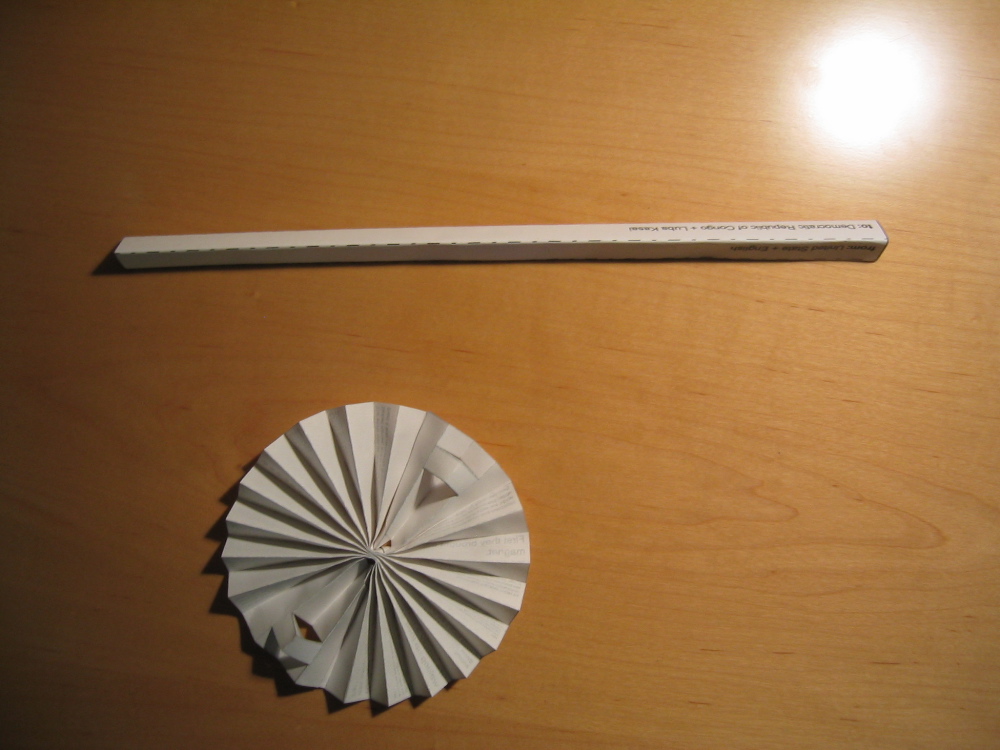

After folding, your message should now have two parts: a pleated circle

and a long, narrow form.

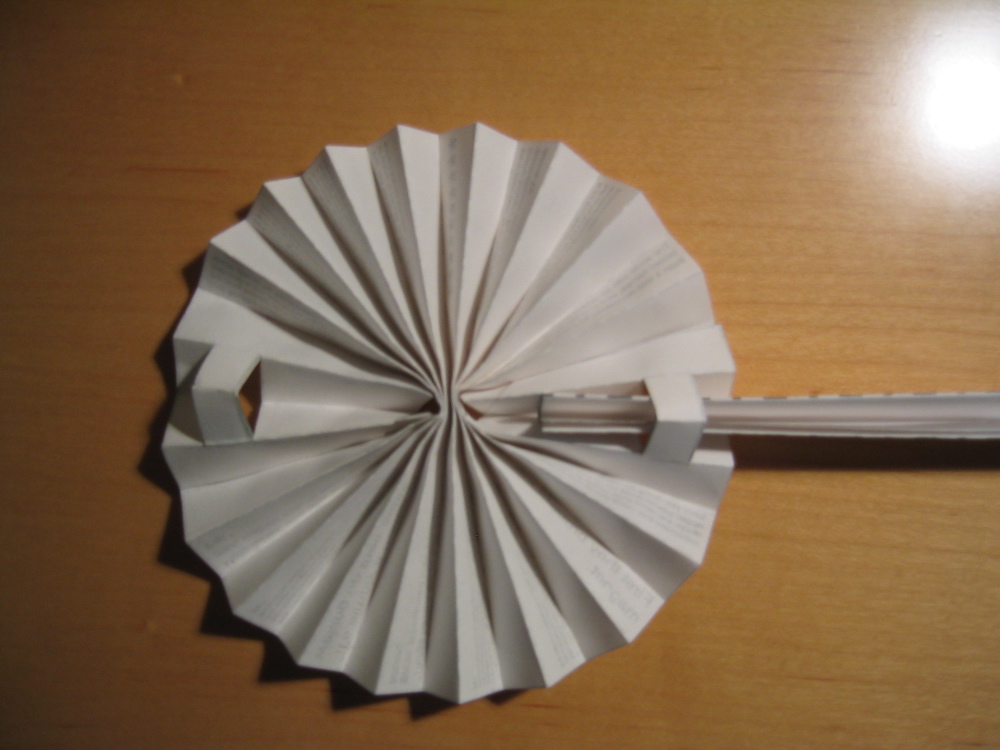

These two parts will be laced together to create a fan. The long

narrow shape will become the fan's handle. Lace it through the

back of the message by pushing it through the two small "loops" created

by the clipped and inverted folds.

Lace it through one "loop" and then push it through to lace it through

the second "loop."

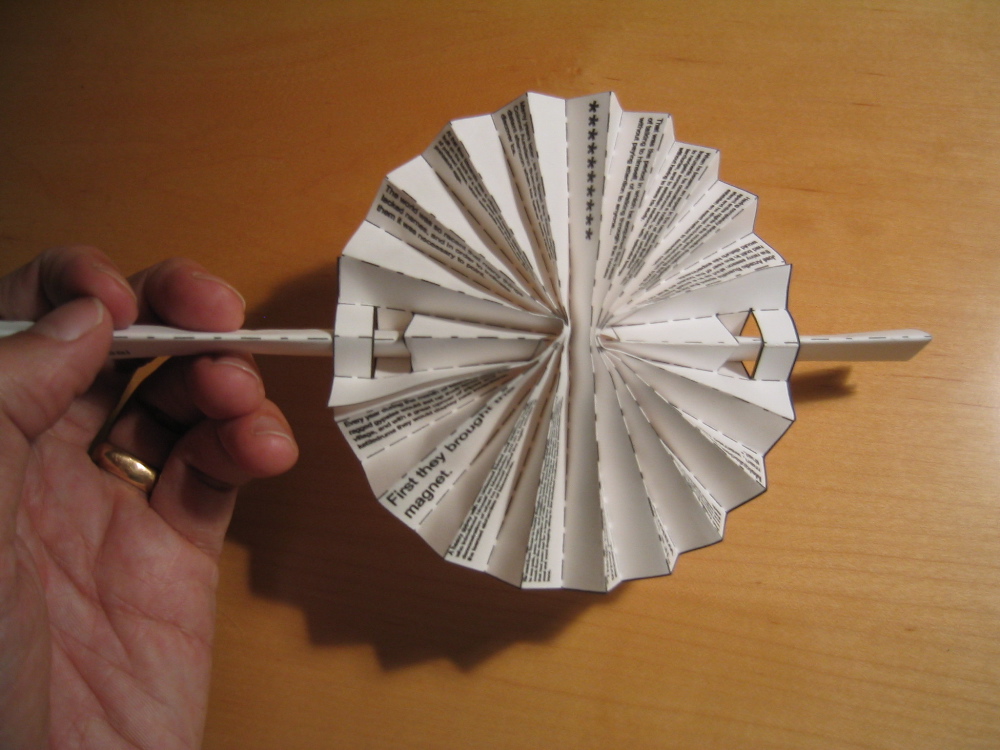

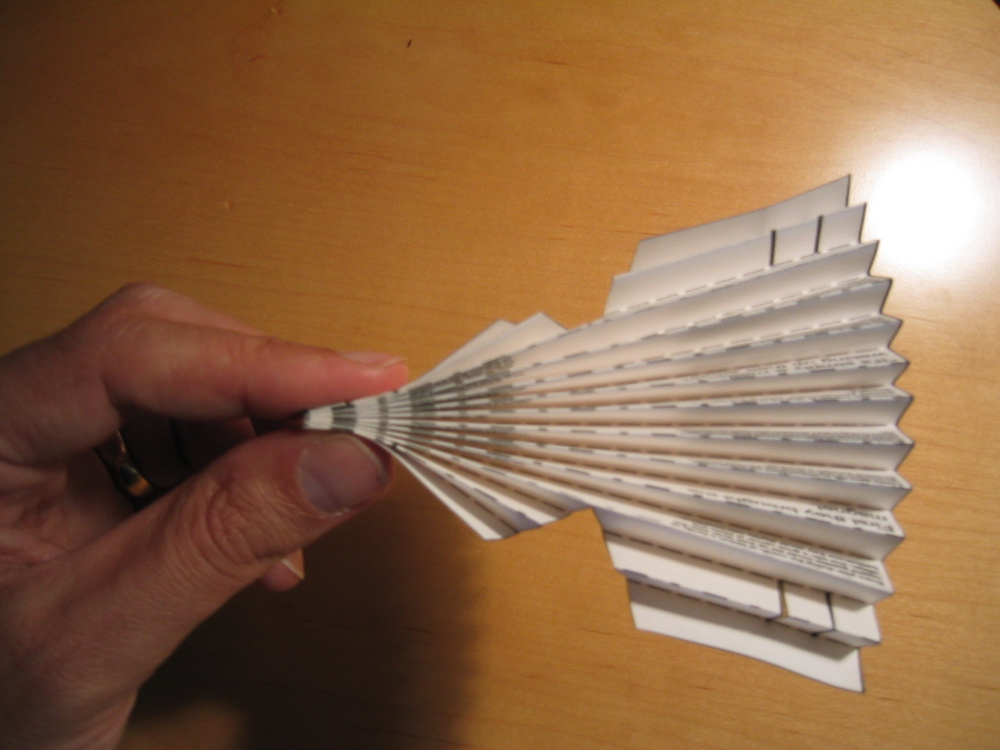

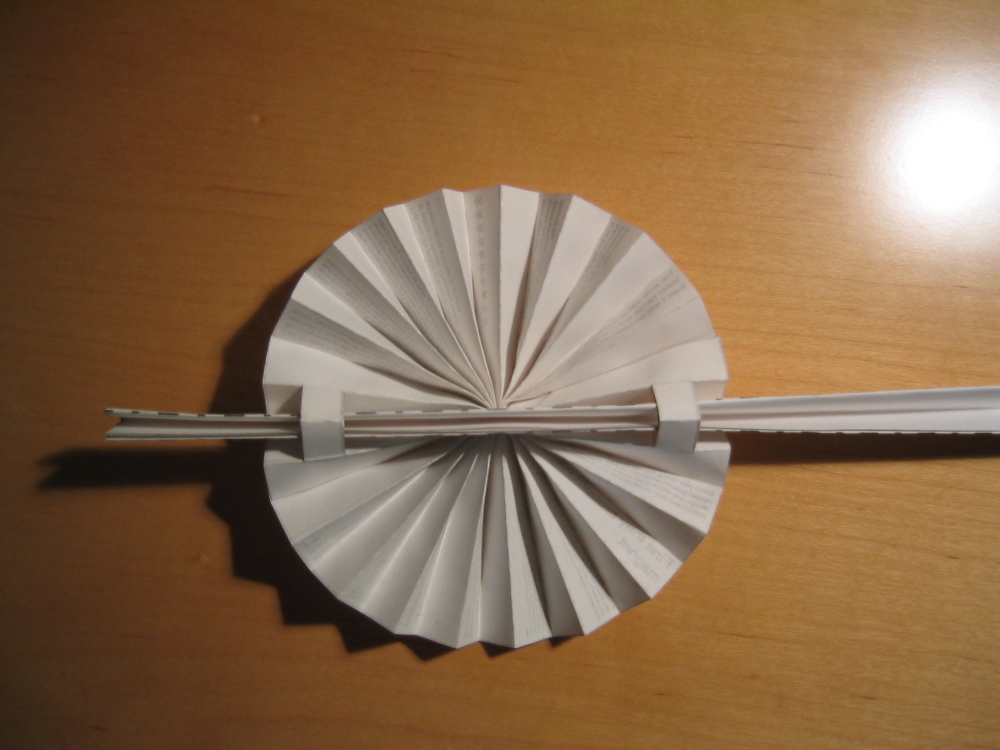

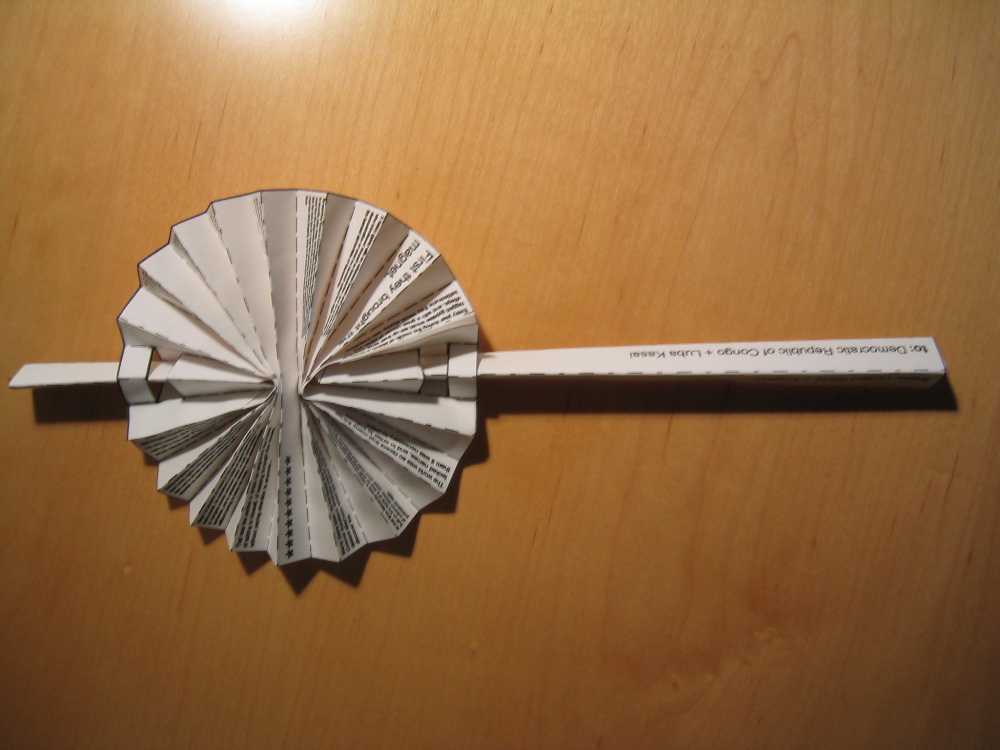

When you've finished, your message should look like the following fan.

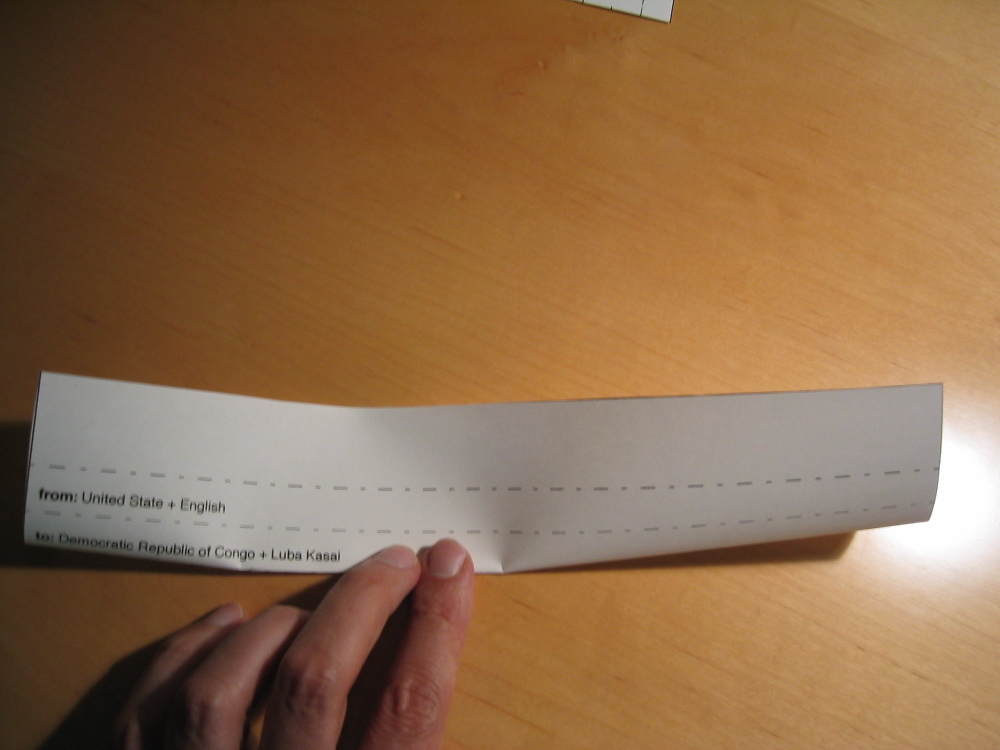

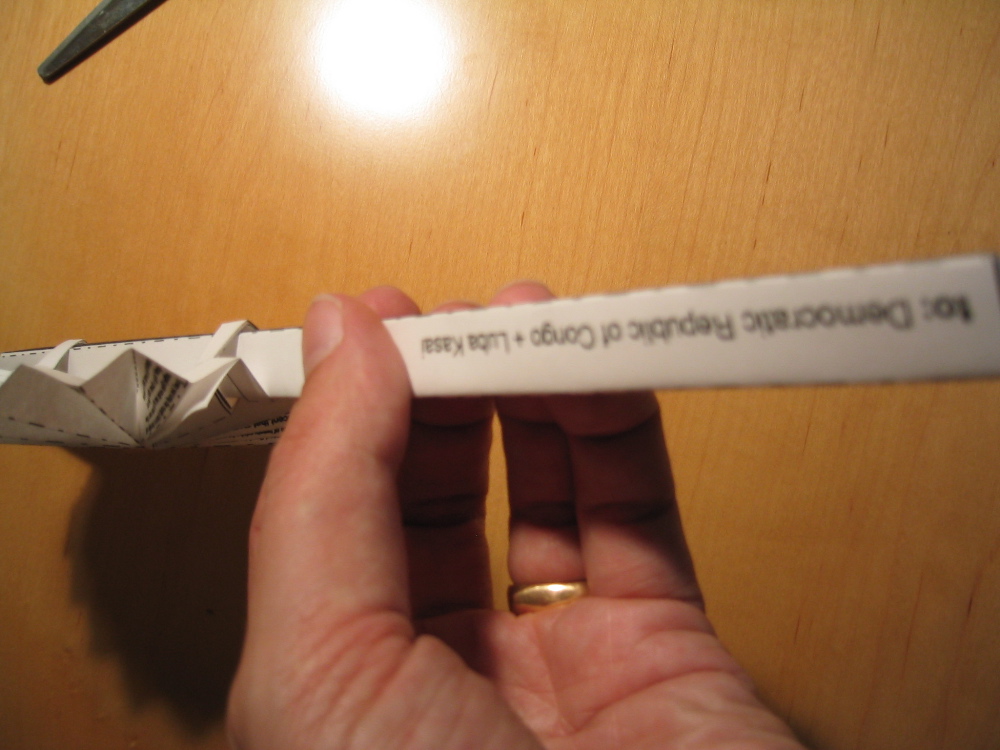

The message destination (place and language) is printed on one side of

the fan handle.

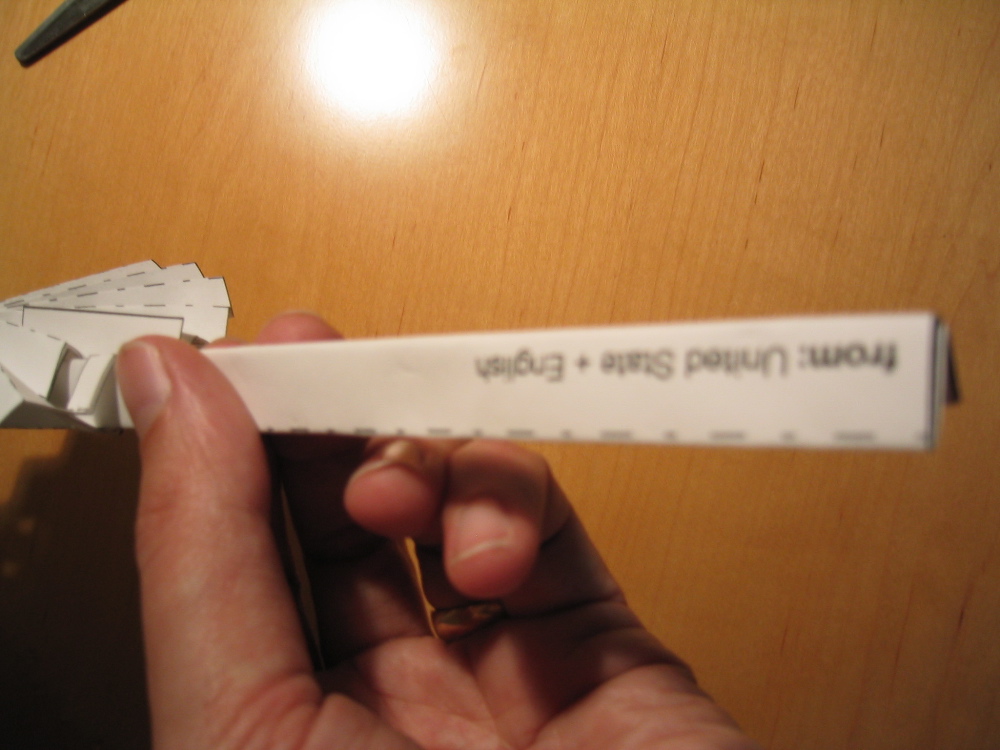

The message origin place and language is printed on the other side of

the handle.

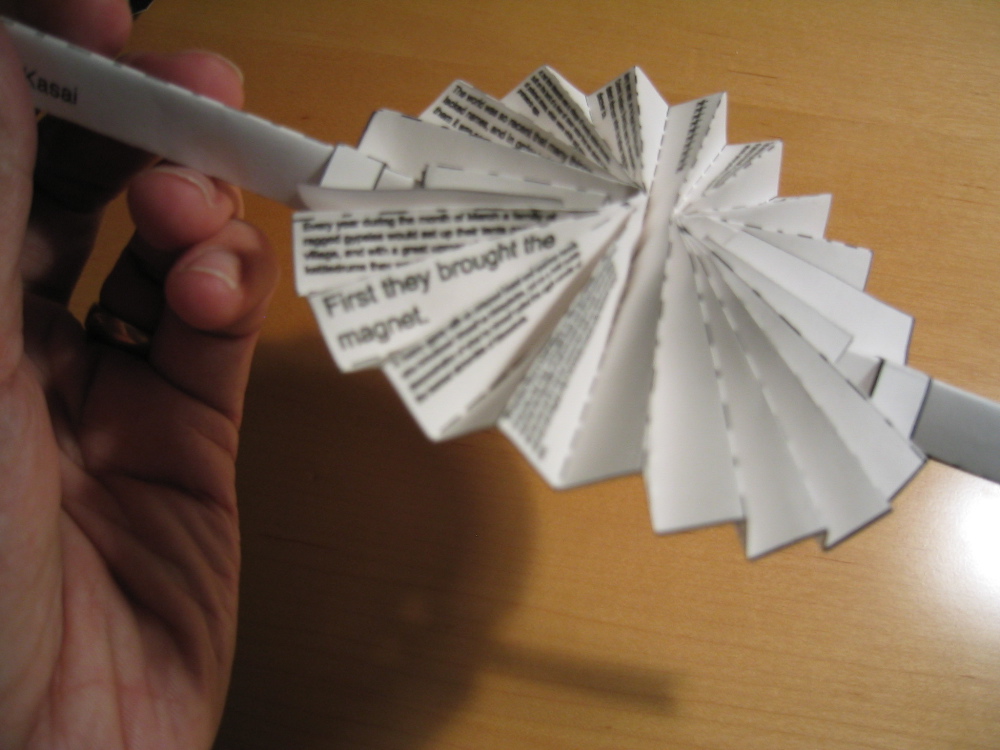

The message itself is printed in such a manner as to make it possible

to read by simply turning the fan around the center of the fan.

That's it! Hand your message off to someone who might know

someone you want it to reach in at the place of its destination.

Or, hand it to someone who might know someone who might be able to help

you translate the message into the destination language.